Municipal Auditorium

“And now we have the Municipal Auditorium. It is almost too good to believe…” wrote Austin Latchaw in the December 1, 1935, edition of The Kansas City Star. Indeed, when it was built, the Municipal Auditorium met the needs for a 20th century city’s functional, multi-use space with the most modern, elegant decor imaginable. The building combined a variety of public-use interior spaces with technically advanced construction and encased it in a massive jewel of Art Deco design.

Kansas City was badly in need of a building to house conventions and large exhibits. The city’s first large convention hall burned in 1900, sending the entire city into a panic, because the Democratic National Convention was scheduled to meet here that year. Within 90 days, a second auditorium was built to house the convention, but it was clear that the structure would not withstand the test of time. City politicians began lobbying for a bond program to support city improvements in the 1920s and, with a large voter turnout supported by the political machine of Tom Pendergast, the “Ten-Year Plan” finally received the support that it needed in 1931. The city bonds were combined with federal WPA assistance funds to erect several civic buildings, including the new Municipal Auditorium.

The block just south of the old Convention Hall was procured by City Manager H. F. McElroy. He dealt directly with business owners, purchasing all of the properties in the block from Thirteenth to Fourteenth, Central to Wyandotte Streets. The architectural firms of Hoit, Price & Barnes and Gentry, Voscamp & Neville began planning the design of the building. Hoit, Price & Barnes was a well-known firm, having designed the Southwestern Bell Telephone Building built at 324 East Eleventh Street in 1919 and the Kansas City Power and Light building built at 1330 Baltimore in 1931. The architects conferred with the Chamber of Commerce’s convention committee to determine the city’s needs for the building.

With all labor and as many materials as possible supplied locally, the construction of the auditorium provided a boost to a collapsed local economy. The Kansas City charter banned the levying of taxes for direct relief to the needy, so the funding of local construction served as a way to battle the Great Depression. In these bleak economic years, the project provided employment to 2000 men. The construction’s final cost of construction was $6.5 million, well over the $4.5 million budget.

The advanced design of the auditorium included the area’s first long-span system of roof support. Using a combination of braced-steel columns and towers that extended from basement to roof in the corners of the building, the interior of the auditorium remained free of central support columns. Roof trusses, weighing in at 1000 tons, were supported solely by the corner columns. Most of the building’s support is provided by the central section of the structure. Some of the heaviest concrete girders and beams available at the time were used for the floor of the arena. The auditorium boasted the most advanced air conditioning and amplification system of its day. Upon completion of the building, the old Convention Hall was demolished and the lot used for parking.

The large building filled its city block with a rectangular mass. Ornamentation took the form of accents placed at the roofline and corners of the boxy building. The flat, limestone expanses of the building’s exterior surface served as a canvas for the spare, modern adornment. Linear geometric designs emphasized the structure’s immensity and punctuated bas-relief medallions that symbolized the intellectual and social purposes of the building. The overall severity of the exterior was softened by the classical figures placed within the medallions. This departure from earlier, more ornate architectural styles was viewed as a very modern style, classified in later years as Art Deco.

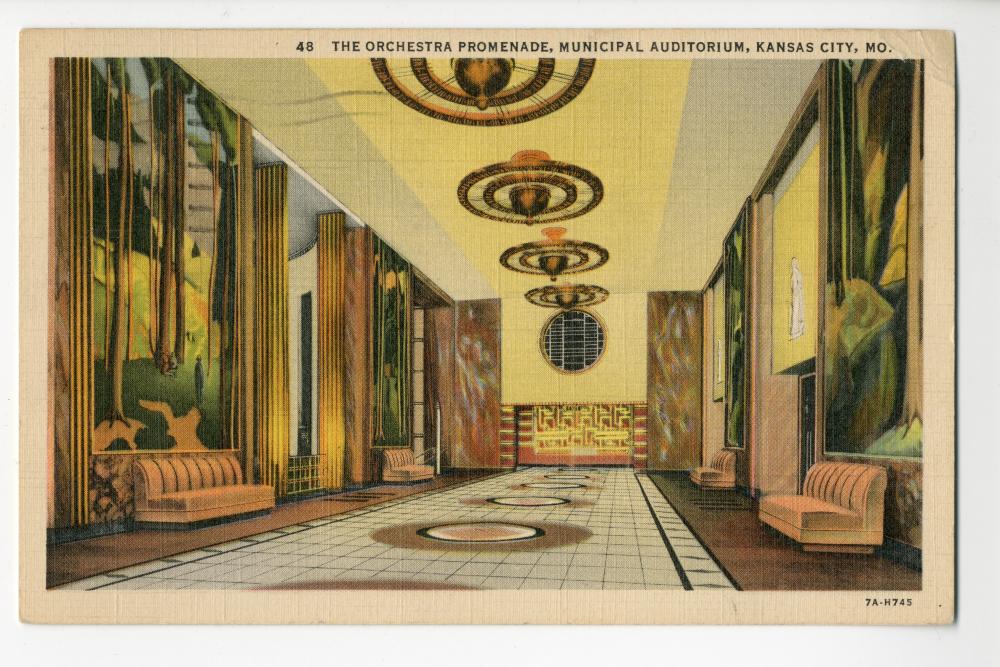

The interior of the Municipal Auditorium was designed to accommodate a variety of uses. After passing through the 13th Street main entrance and the ticket lobby, one entered the grand foyer, which led to the main floor of the auditorium. Lighting fixtures, interior colors and tiled floor designs invoked a modernistic flavor that continued the Art Deco theme established on the building’s exterior. The main arena seated up to 14,000 people in green fabric seats that allowed ticket-holders to have an excellent view from any location in the arena. Ramps with wide, easy grades helped move crowds from one level to another. The lower level of the auditorium contained an exhibition hall surrounded by a mezzanine. In addition to its large spaces, the building contained a number of smaller committee rooms to be used for recitals, lectures and meetings. The overall effect of the interior was one of functional, yet modern, simplicity.

The Municipal Auditorium opened to the public on December 1, 1935. The dedicatory event was the opening of the motor show, an affair that effectively showed off the large and contemporary space. The twin goals of the Ten-Year Plan were to provide work for local laborers and to ready the city for the future. By “giving to Kansas City an enduring and impressive monument to its public spirit,” as The Kansas City Star proclaimed, the architects and developers of the Municipal Auditorium brought the city national recognition as the site of one of the finest such facilities in the country.

The Little Theatre and Music Hall, ensconced within the complex, were completed under separate contract on June 14, 1936. The entrance to the Little Theatre was located on 13th Street, immediately to the west of the entrance to the main arena. One entered the Theatre, which seated 3000, by ascending a grand stairway and entering space that occupied the area above the ticket lobby of the auditorium. The elegant Music Hall, built as a home for the Philharmonic Orchestra, was entered on 14th Street. It sat 2500 patrons in elegant splendor, amid tones of mulberry, green, and gold. Walls were adorned with murals throughout.

Many Kansas Citians saw Municipal Auditorium as a key in the city’s future nationwide reputation. It was seen not only as an important regional and Midwestern gathering place, but also as a place where events of national importance would take place. In his 1935 article praising the auditorium, Austin Latchaw wrote:

“Great political decisions will be made here, decisions perhaps affecting vitally the subsequent history of the nation. Science will mark progress within these walls. Religious bodies will gather here to renew their faith, to gain fresh inspiration. Great educational bodies here will confer on the problems of their field. The business world will discuss its policies and industrial products will be exhibited to demonstrate the evolution of manufacture.”

The possibility that one building could bring so much to Kansas City surely made the Municipal Auditorium the local monument of its day.

A version of this article previously appeared at http://www.kchistory.org/content/municipal-auditorium-profile

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.