"The Castle on the Hill": Lincoln High, Racial Uplift, and Community Development During Segregation

“The black schools [in Kansas City] were much better than they had any right to be, partly because they were full of talented teachers who would have been teaching in college had they been white, and partly because Negro parents and children simply refused to be licked by segregation”– Roy Wilkins, reporter for the Kansas City Call.

Roy Wilkins’s statement about education in the Kansas City area aptly summarizes the unjust obstacles that segregation created for black students, their parents, and educators at the segregated schools of Kansas City. Before the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared separate public schools for white and black students to be unequal and unconstitutional, black communities and activists made personal sacrifices in their fight for quality educations; they arguably had to do so afterward, as well. The African American schools that managed to stay open in the Kansas City area during segregation did so despite discriminatory policies that frequently underfunded, closed, and overcrowded schools.

Until 1954, historian Kevin Fox Gotham notes that Lincoln High School and its feeder junior high schools were the only schools in Jackson, Clay, and Platte Counties that provided post-elementary education to black students. Only six out of 61 “African American settlements” in those three counties provided elementary schools for black children. Before 1929, the state exempted school districts from providing schools for black students if enrollment fell below 15; if attendance dropped below eight, the school was eliminated entirely. After 1929, districts had the option to discontinue schools for black children, no matter the number enrolled. There were frequent school closings, particularly in rural areas in which counties claimed they had insufficient funds to maintain separate school facilities. This left many African American children without proper access to education.

Frequent closings and limited numbers of institutions meant that parents either had to move to residential areas close to black schools, send their children to live with friends or relatives in these areas, or require that their children travel long distances to school. Some rural students in Missouri commuted to Lincoln High from an hour away. Commuting carried other hurdles, including instances of reported teasing of rural students from their city counterparts; some rural students did not have electricity or running water, which seemed to make them a target as inferior, uneducated, and poor.

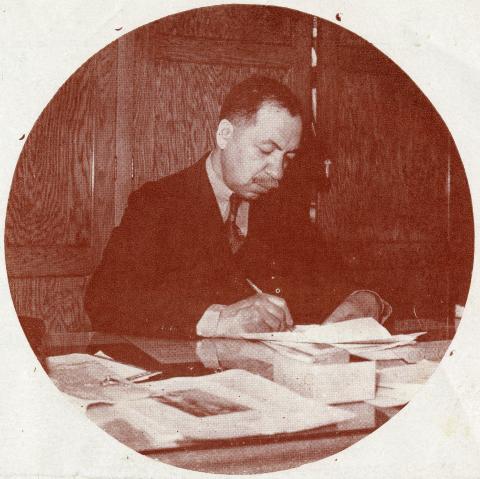

Gotham further argues that discriminatory housing policies and de jure segregated school systems “formed a mutually reinforcing set of institutional barriers that prevented blacks from participating in the suburbanization process that benefited millions of whites.” That is, while black migrants were funneled into segregated areas of Kansas City by housing practices, such as J.C. Nichols’s redlining policies, the segregated school district also ensured that black parents resided close to (in the case of Lincoln High) the only available African American high school serving the Missouri side of Kansas City. Practically, when Lincoln High needed a new facility, H.O. Cook, principal (1921-1944), advocated that the new building be located somewhere near the middle of 25th, 27th, Vine, and Paseo streets because it would be central for approximately 63 percent of the city’s black students. That area was near the business center of the segregated community. The further a parent lived from that center, the more difficult it would be to access all-important opportunities for education and advancement.

Toward a Quality Facility

Gaining a proper facility for Lincoln High was a complex and extremely long process. Established in 1867, Lincoln School (as a grade school) was the first school for black children on the Missouri side of Kansas City. It was originally in a building rented from the Second Congregation Church, located in what is now 10th and McGee Streets. Initially, adding a high school curriculum and building space proved difficult. David Victor Adolphus Nero, principal in 1881, proposed a detailed curriculum for a black high school to the Kansas City Board of Education, and while the board did authorize the inclusion of select high school courses at Lincoln School, they also simultaneously transferred Nero to Sumner School in the West Bottoms, likely out of retaliation.

In 1890 a separate building was built at 19th and Tracy, establishing Lincoln High School as the first all-black high school in Kansas City, Missouri, with G.N. Grisham as principal. (In 1910, Joe Herriford would replace W.W. Yates as principal and pressure the Board of Education to avoid further confusion about the two Lincoln schools by renaming the elementary school after Yates.) Grisham joined scholars in the American Negro Academy, an organization of African American intellectuals advocating higher education, the arts, and sciences for black Americans as means for advancement and racial equality. The organization’s principles were a model that was articulated further by W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of the “Talented Tenth,” an emergent middle and professional class that would develop leadership and advancement for African Americans.

The ANA was active from 1897-1924, and aligning with the ANA’s ideals, Grisham as an educational leader took issue with Booker T. Washington’s model that advocated menial and trade labor education for African Americans. Instead, Grisham’s remarks, reproduced in Colored American in 1897, validated the black scholar’s role in society. Grisham’s vision for black scholars and black public intellectuals marked a shift toward conceptions of Lincoln High School as an institution of advanced learning with a Du Boisian approach to education, rather than an educational center that focused on producing trade laborers. While Lincoln High continued to offer vocational training throughout the Pendergast years, the inclusion of vocational training and the manual arts within the curriculum continued to cause tensions about Lincoln High’s educational role. Trade courses seemed necessary, but leadership at the institution focused on continued higher education as a path to create the nation’s top black leaders and intellectuals.

In order to create emergent leaders in Kansas City’s African American community, Lincoln High advocated for the humanities and sciences. Even in the 1920s and ‘30s, while Lincoln High continued to offer trade courses such as mechanical drawing, cabinet making, carpentry, and masonry, the core curriculum at Lincoln High emphasized English, science, history, and mathematics. Although all students were required to take these core classes as the bulk of their coursework, the 1927-1928 student handbook did say that students who did not plan to attend college could substitute two credits from the “non-solid” courses (typewriting, home economics, physical training, and the arts) for mathematics requirements. English required the most credits, at six, and history classes were also prioritized with inclusion of black history and culture. While it is unclear exactly which topics and works were studied under the umbrella of African American history, this inclusion speaks to the role Lincoln High held as a center that sought to prioritize its students’ histories and experiences. Alumni Jeremiah Cameron would announce years later that as Lincoln High students, “we knew about Negro music, Negro literature, and Negro achievements.”

Lincoln High’s enrollment continued to grow rapidly as Kansas City’s black population increased, but the facility increasingly fell short of the demand. Expansions were made to Lincoln High, but the building at 19th and Tracy was underfunded, lacking resources such as math and science lab equipment, and severely overcrowded. For over a decade, principal H.O. Cook, Lincoln High faculty, and the broader black community campaigned for a new facility. In 1927, the Board of Education purchased “Castle Ridge,” at 21st Street and Woodland, as the school’s new site, and the Board announced the project in fall of that year. The bonds issue vote failed to pass, though, and consequent lack of funds delayed construction further. Meanwhile, two new white schools were already under construction, with plans for a new high school for whites at 48th and Flora (Paseo High School).

In a 1926 editorial for the Lincolnite, the high school’s newspaper, then-student Lucile Bluford wrote about the delay of funds and construction, placing blame on the all-white school board for the stalemate:

The opposite race has six high schools, in which to educate its children. . . . They [the school board] have been going to do this for the last two or three years. Surely it cannot be thought the Negro citizens do not deserve a new school. Has not Lincoln as large a percentage of pupils attending college as any high school of the city? Are not two of Lincoln’s graduates on the University of Kansas Honor Roll? Still with these facts we are neglected.

Even as much-needed renovations at Lincoln High stalled, the Pendergast machine has largely been credited with using its influence to ensure successful bonds votes for funding issues such as General Hospital No. 2, Kansas City’s black public hospital. That structure was completed in 1930 after years of overcrowding and inferior health care for black patients, and also as the Democratic party began distancing itself from the Ku Klux Klan and shifting toward liberalism. Self-interest at General Hospital No. 2, specifically in job appointments, motivated the Pendergast machine to push the hospital’s bonds vote. Political machines did not, however, have the same access to Kansas City’s school board. School board election nominees were always white, but candidates from both parties ran uncontested for an evenly divided number of seats. The school district would have held hundreds of positions through which Pendergast could have controlled and rewarded adherents to the machine, but David Hanzlick attributes Pendergast’s “hands off” approach to members of the board being historically established and prominent members of Kansas City’s business establishment, as well as a firm tradition of uncontested school board races.

It may be significant, then, that the district’s school board did not face pressure from the Pendergast machine to advocate for a proposition that black voters supported, a new black high school; and when the board belatedly acknowledged the plight of Lincoln High, they lacked the backing of the machine, which might have gained enough support from white voters for the school’s bonds issue. Ultimately, it took a decade-long fight for a new building, years after the finished construction of General Hospital No. 2. Despite the disappointing lack of support from the school board and white voters, the black community continued to rally around Lincoln High, even as facility conditions worsened.

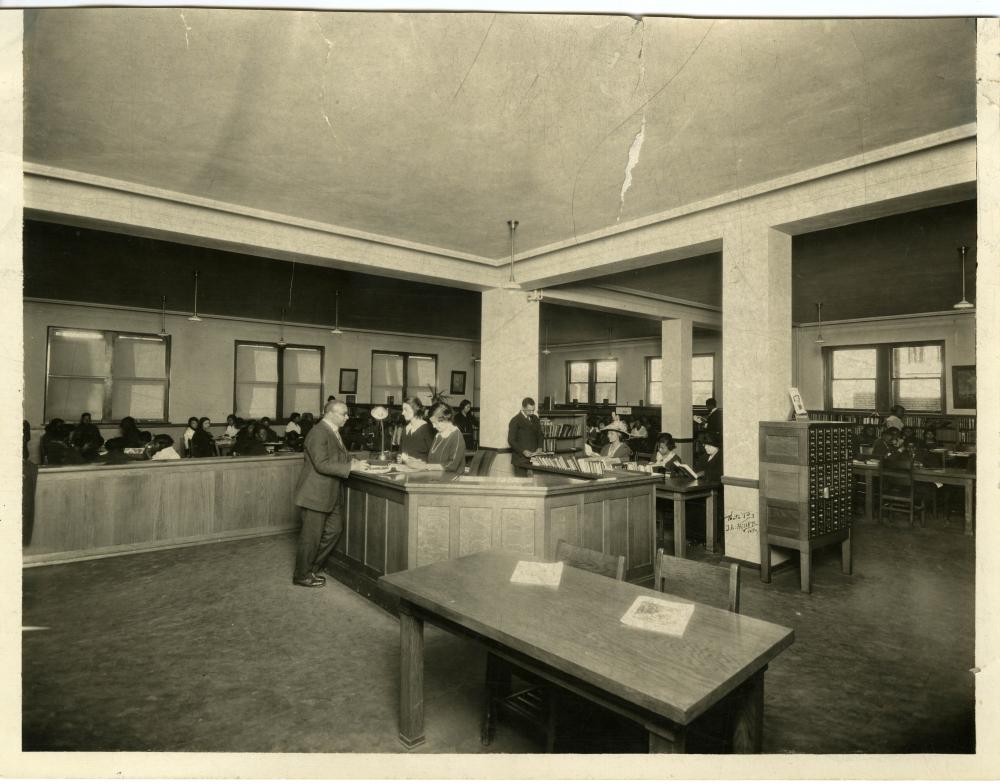

Migration into Kansas City and school closings had continued to augment the student population over the last two decades, and 1,100 students were crowded into a building facility made for 800. Makeshift classrooms had been set up, attached to the main building and consisting of wooden frames, while some classes were held in hallways and stairwells. Teachers lacked desks, and the gas stove in the domestic science classroom leaked horribly. Still, amid years campaigning for a larger and better facility, support for Lincoln High School and black education continued to gain strength among the black community in Kansas City; residents, for example, formed the Negro School Improvement Association. This allowed members of the black community to put pressure on school board officials to make progress, and the organization was able to mediate and monitor educational conditions, including plans for a branch of the public library at Lincoln High that was open to all Kansas City residents.

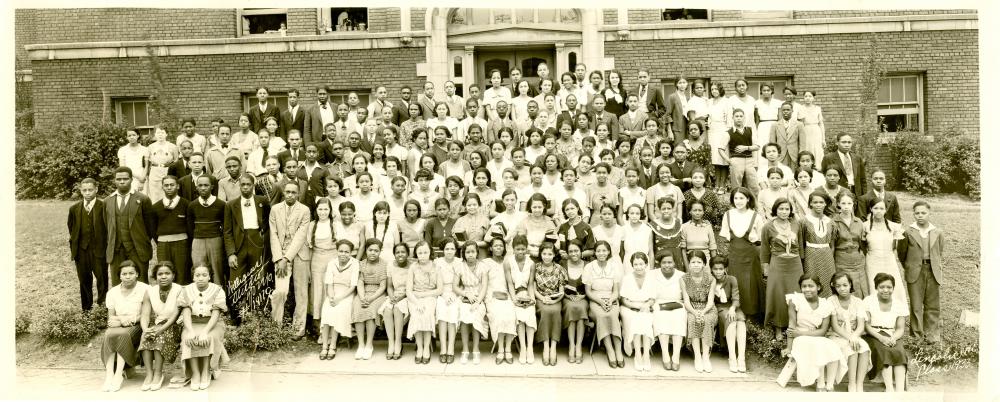

Construction finally began in 1935, after it was apparent that the board could delay construction no further. Once it finally opened for the 1936-1937 academic year at 2111 Woodland Avenue, the new Lincoln High facility had cost $700,000 to construct. It accommodated 1,100 students much more comfortably, contained two gyms and a swimming pool, updated science labs, art and music rooms, and a two-story auditorium. The “Castle on the Hill,” in its modernity, could finally compete with (and surpass) many white schools that had previously received better and more immediate resources so long denied to Kansas City’s black population.

Educational Legacy and Racial Representation

At the height of segregation and amid continual challenges for proper resources and facilities, Lincoln High still drew nationally renowned black artists and educators, successful and prominent individuals who could have been teaching at any prestigious university in the country but for their race. Before his most famous illustrations had been completed, Harlem Renaissance visual artist Aaron Douglas taught art for two years at the school. He later became known for his contributions to the covers of Opportunity and Crisis, numerous book covers, the sole issue of Fire!! (ironically, after publication of the first issue, the magazine's headquarters burned down), and murals still visible at Fisk University.

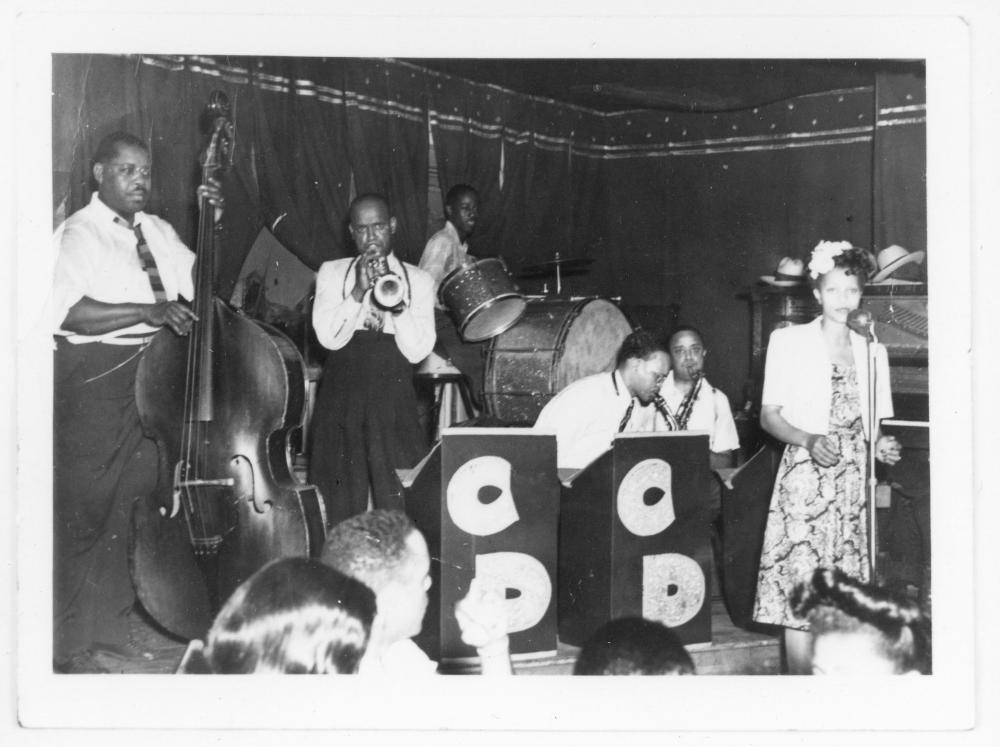

Acclaimed band leaders also taught at Lincoln High, cultivating music skills and future musicians who surpassed expectation. N. Clark Smith, musician, composer, and band leader, taught music and led Lincoln High’s band and orchestra from 1916-1922. He trained several of Kansas City’s early jazz musicians. When Smith’s instructional skills became so renowned that the George Pullman Porters offered him a lucrative position instructing hundreds of porters in music, he left Lincoln High and was later replaced by William Levi Dawson, who has been credited for composing the first symphony by a black man that used African American themes. Both Smith and Dawson worked at Tuskegee Institute prior to Lincoln High, and Dawson went back to Tuskegee after four years of teaching. During these years, Lincoln High educated Walter Page, Julia Lee, Harlan Leonard, Leroy Maxey, Lammar Wright, Jasper Allen, and DePriest Wheeler, among others. Another of Smith’s successors, Alonzo Lewis, taught Eli Logan and Charlie Parker.

These teachers were also engaged with the broader black community of Kansas City. J. Oliver Morrison, for example, taught drama and oratory at Lincoln High from 1918 until his death in 1949 and organized a community chorus in the 1920s that performed at functions within the broader black community. In 1933, he also founded a local theater group, the Morrison Players, through the Kansas City Urban League.

Dr. David N. Crosthwaite preferred teaching over a physician’s career, likely because establishing a medical career required navigating local politics, and he taught chemistry and science at Lincoln High beginning in 1895. Crosthwaite also tutored black candidates for civil service examinations, and he and his wife, Minnie, were active in the broader community. Minnie Crosthwaite, in fact, became the first black social worker in Kansas City, worked at Wheatley-Provident Hospital, became director of its outpatient clinic, and served as Wheatley-Provident Hospital Auxiliary president for 20 years. The Auxiliary’s annual fashion show, implemented by Crosthwaite, raised money for the hospital.

Because segregation instilled barriers that kept highly qualified African Americans from teaching at then-white and segregated universities, Lincoln High gained such impressive leaders and instructors for their student body. (It should also be remembered that black women, were, of course, teaching at Lincoln High during this time, but were not re-hired after marriage, largely preventing them from holding elevated levels of leadership within the school itself.) Out of that injustice, numerous young black people were educated by artists, doctors, and teachers who were, by any standard, overqualified. Their impact for the Kansas City area and Lincoln High community was profound and simultaneously a side effect of segregation.

In addition to producing impressive leaders, musicians, journalists, and educators, Charles Coulter writes that particularly during the 1920s and 1930s, black schools were a source of “pride” and "instruments of community and racial formation.” Lincoln High united individuals in the broader black community by hosting weekly public forums and often inviting ministers and civic leaders to speak at these meetings. Some notable speakers included newspaper editors Nelson Crews and Chester Franklin. Many events were also sponsored by Kansas City’s chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). The forums allowed community members to begin discussions related to local issues and inequity, engage various intellectual topics, and to provide entertainment.

Henrietta Rix Wood argues that Lincoln High graduates were an elite group, joining the ranks of W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth” leadership that would strengthen the middle-class community of Kansas City. During the early 20th century, only 10 percent of adolescent African Americans were enrolled in high school in Missouri, and only 2 percent of African Americans enrolled in higher education. While Lincoln High maintained a technical track, those students continuously enrolled at Lincoln High gained and held a level of privilege many of their contemporaries did not. Some students reported working arduous summer jobs, often work that was underpaid, physically difficult, and menial. For these students, the school year was a reprieve from domestic, servile, and manual labor. While exact numbers and subsequent careers of graduates during the 1920s and 1930s remain unknown, certainly some alumni went on to join the ranks of new black professionals and businesspeople in Kansas City. And, certainly during the Jim Crow period, local African American professionals were invested in Lincoln High’s role in developing upward mobility and establishing race pride, solidarity, and equity.

Lincoln High created an environment that charged its students with learning and striving for upward mobility as representatives of their race. That is, the rhetoric surrounding practices at Lincoln High, including addresses by visiting officials and editorials/yearbooks, often prioritized the community over the individual. Local black professionals customarily spoke at annual opening assemblies, giving encouraging speeches to set the tone for the school year and to remind students of their potential to affect broader cultural change. This charge was implicitly, and at times explicitly, tied to race, representation, and equity.

One such address occurred in September 1940, when prominent African American lawyer William C. Hueston advised the Lincoln High student body at the start of the school year. He said, as quoted by Coulter,

This high school represents our race in the contest that we are to have in this country and let it be understood that a contest is to come and you must decide for yourself whether or not this test is to be won by you. You are not here to get an education for your own use. It is for something in which we are all interested and the question is whether or not you as representatives of the race of ours are going to measure up.

Hueston’s address verbalized contemporary concerns. It centered the fight for the end of segregation and discrimination, looking forward to political equality. As an intellectual and community center, Lincoln High was charged with creating leaders for a broader, national movement of advancement, and its students were reminded of their perceived responsibility to their community. His words prioritized uplift for the entire race, rather than individual advancement through education. Through this lens, individual students were held to a high standard of professionalism, leadership, and activism.

Racial solidarity and community was also reflected in the school’s first student handbook (1927-1928). The handbook, in many ways, met the conventions of any given school’s handbook, but it warrants closer examination for what it illustrated about expectations for Lincoln High students as both members of a student body and as members of the broader African American community. This first handbook leads with a preface from that year’s student council, whose “special committee,” chaired by Lucile Bluford, spearheaded the effort in the hope “that it will inspire and guide” students and “encourage them to partake in the various activities of the school.” H.O. Cook’s foreword also described student handbooks such as Lincoln High’s a “necessity . . . for the purpose of helping in the adjustment of students to the practices and ideals of the schools, and, second, to set forth to the public, the activities, courses and special features of the life of the school that make it an attractive institution.” The handbook’s purpose, then, was not only to guide and instruct students to navigate the rules and culture of the school, but also to supplement and strengthen the school’s image to the “public.”

Not surprisingly, the handbook provided much of the instruction one would expect from a student handbook. It outlined compulsory courses and requirements for graduation, preparation for college, and advisory groups, as well as general rules. Of particular note, however, was the text’s emphasis on engagement both within the classrooms of Lincoln High and extra-curricular communal activities within Kansas City’s black community. Students were encouraged, for example, to buy the “Activities Ticket,” a booklet that contained tickets and coupons to school activities (such as sports events, plays, and social gatherings.) The booklet also, significantly, included “a coupon worth the membership fee of the NAACP, the Junior Red Cross, and the Athletic Association.” Within the Activities Ticket, then, Lincoln High students were directed to participate not only in the school’s extra-curricular activities, but also in active work within the black community, through organizations such as the NAACP.

The local Junior Branch of the NAACP was fostered by Lincoln High, and according to the handbook “contribute[d] annually” to the larger body, maintaining national affiliation with the NAACP. Besides working in solidarity with the “Senior Branch,” the handbook described the Junior Branch as “foster[ing] Lincoln-Frederick Douglass programs in February, Baby Contests, Social Get-togethers, etc.” This branch also, of course, planted seeds for future adult alums to participated in the Senior Branch and to continue to contribute throughout adult life. A 1928 publication of the school yearbook, The Lincolnian, described membership increasing over time because “gradually it is being instilled in the minds of the students that they can be of great service to the race in later years if they are trained now.” Whether individual students joined or declined, the student body viewed participation in the NAACP as a life-long contribution to bettering the race.

Lincoln High built a central foundation for its students and Kansas City’s black community. The circumstances of segregation and discrimination created the school and simultaneously curtailed funding, resources, and proper facilities in favor of white schools. Despite institutional barriers, though, Kansas City’s black community supported and claimed Lincoln High as a prestigious educational and cultural center. These community members continued to insist on better educational opportunities and conditions: they moved their lives and families for closer proximity to black schools, they campaigned for better resources and updated buildings, and they physically came together as a community within that space, holding forums and debating local issues. Part of Lincoln High’s level of prestige stemmed from its excellent educators, who also created talented artists and professionals, but local businesspeople also held ties to Lincoln High and instilled a sense of racial pride and middle-class aspirations. One central narrative surrounding Lincoln High at the time was one of hope and community: hope for better educational opportunities and resources for African Americans, hope for uplift and equity, hope for a strengthened community and black middle class.

After the 1954 Supreme Court verdict in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, Kansas City slowly began integrating its school system. Due to ongoing, de facto geographic segregation, Lincoln largely continued to be an all-African American school, as did several feeder schools. During the Pendergast years, the materials and products from that institution reflected the desire for excellence and equality, and they centered not the individual, but instead the entire rest. Lincoln High produced numerous leaders and professionals, and it bolstered the surrounding community at the height of Jim Crow. Despite segregation, and because of consistent support from Kansas City’s black residents, the institution became the “Castle on the Hill.” Lincoln College Preparatory Academy, as it has developed since then, serves as a magnet college preparatory school and retains the initial legacy set by Lincoln High. According to the Academy’s website, after desegregation, “The opening of some previous white schools represented the outward migration of black families from previously restricted corridors. . . .” For those who attended the Woodland building, it still remains “the castle on the hill.”

Additional support from the Missouri Humanities Council.<\p>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.