Confronting Injustice: Lucile Bluford and the Kansas City Call, 1939-1942

On February 3, 1939, thousands of subscribers to the Kansas City Call opened the weekly newspaper published by and for African Americans and scanned the front page. At first glance, the reports in the national edition that reached as many as 100,000 black and white readers in Missouri, Kansas, and 13 other states seemed typical: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had rejected a federal anti-lynching bill as inadequate; heavy-weight boxing champion Joe Lewis had recently defeated challenger John Henry Lewis at Madison Square Garden in New York City; the presiding bishop of the African American Methodist Episcopal Church had died; and black Republicans had met in Kansas.

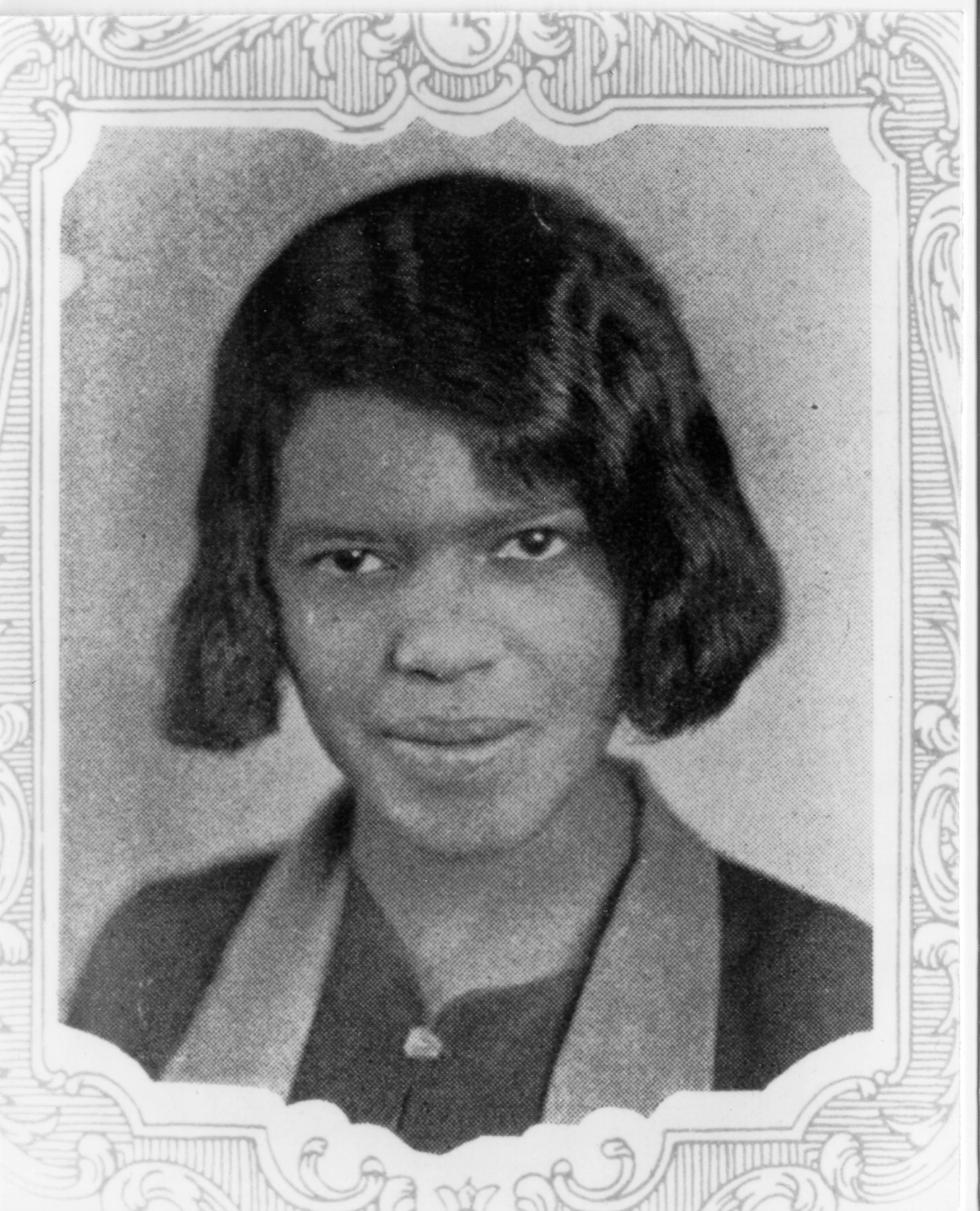

As readers continued to peruse the front page, however, they saw a remarkable series of six stories under a banner headline, “M.U. Rejects Woman Student.” Positioned prominently was a first-person account by Lucile Bluford, the 27-year-old African American managing editor of The Call, about her historic actions five days earlier when she tried to enroll in classes of the graduate program in journalism at the racially segregated University of Missouri in Columbia (MU). The headline of Bluford’s report was “Nothing Will Happen When Negro Student Is Admitted to M.U.” In the first paragraph, she reiterated that message: “Those who fear trouble if a Negro student attends the University of Missouri may rest at ease—there will be no trouble, no violence of any kind. That is the one significant thing that my attempt to enroll brought out.” Reassuring African American readers who anticipated hostile reaction to her appearance at MU, she also defied the expectations of some whites with her assertion. Bluford’s second first-person story appeared in the lower right corner of the front page, next to a column, “Why I Applied to Missouri U.” A conventional news story and two other short items about the incident provided more details on the front page. On an inside page of this issue was a seventh story, “Desired to Enter M.U. Long Time.” In an era when reputable newspapers rarely featured first-person stories or reports with bylines, this series was uncommon, but this was an extraordinary event. Trying to persuade readers to support the national campaign for educational equity, Bluford and The Call carried on the tradition of African American women journalists and the black press that had advocated racial rights for decades.

That campaign was well under way when Bluford made headlines in The Call, which chronicled other African Americans who were challenging the racist policies of institutions of higher learning during the 1930s in the United States. Before Bluford tried to cross the color line at MU, Donald G. Murray, of Baltimore, attempted to enroll in the University of Maryland Law School, and Lloyd C. Gaines of St. Louis sought admittance to the MU Law School. Although The Call and other African American newspapers such as the Baltimore Afro-American and the Chicago Defender documented the actions of Murray and Gaines, the coverage was standard objective reporting that differed dramatically from Bluford’s first-person accounts. Ascertaining whether any African American who tried to enter segregated institutions of higher education wrote first-person accounts for black newspapers before Bluford is difficult, but scholarship suggests that none of the early plaintiffs were journalists. Consequently, Bluford’s action may be unique. Capitalizing on her capabilities as a reporter and The Call’s capacity to serve as an argumentative forum, Bluford and The Call participated in what historian Leslie Brown calls the “persistent protest,” the crusade for African American rights that began decades, if not centuries, before the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s.

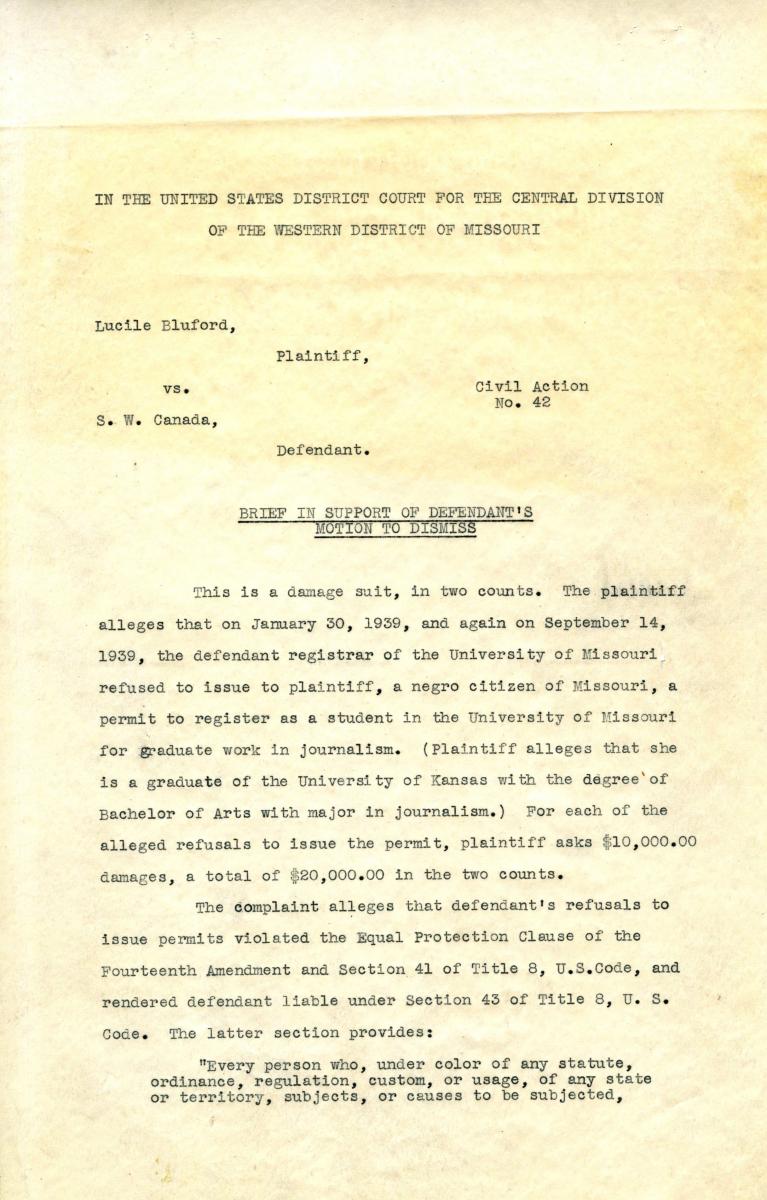

This essay analyzes Bluford’s initial reporting on her effort to enter MU, her commentary on her failed civil lawsuit in May 1942, and the announcement of the newspaper’s fundraising campaign for African American education in the same month. The facts of Bluford’s three-year crusade to enroll at MU are known: she repeatedly tried to enroll at the university and pursued three lawsuits, losing the last one in April 1942. The fact that she and The Call collaborated to influence readers’ responses to the quest for African American educational rights has not been acknowledged or analyzed.

By the time that Bluford made news in 1939, she already was a civil rights advocate and experienced journalist. Growing up in Kansas City, she attended NAACP meetings with her father, John H. Bluford, who was a teacher at Lincoln High School, the only public high school for African Americans in the city until 1936. Bluford went to Lincoln in the 1920s, where she was an officer of the junior branch of the NAACP and an editor of the school newspaper. In 1926, she wrote a signed editorial for the Lincoln newspaper that called for a new African American high school and questioned the Kansas City board of education for failing to build it. Barred from attending racially segregated MU, Bluford studied journalism at the University of Kansas in Lawrence and reported for the KU student newspaper, as well as The Call during her summer breaks.

At The Call, Bluford worked with the publisher, Chester Arthur Franklin, and the news editor, Roy Wilkins. A native of Texas, Franklin helped his family run a newspaper in Denver before he moved to Kansas City and founded The Call in 1919. Scholars’ views of Franklin vary. Sherry Lamb Schirmer refers to Franklin as “the spokesman for race men and women in Kansas City,” characterizing this group as people who identified themselves “proudly as Negroes” and “defined themselves by their deeds.” Thomas D. Wilson asserts that Franklin “believed civil rights depended on economic success, and economic success depended on the Protestant work ethic. When African Americans failed to display this ethic, he chastised them.” Wilson also contends that Franklin regularly took issue with the stances promoted by the NAACP in its publication, The Crisis. Charles E. Coulter maintains that in the early years of the newspaper, Franklin was more conservative than many of his readers. Franklin tended to favor running sensational stories of sex and scandal in the early 1920s that boosted readership. During Wilkins’s tenure, he served as secretary of the Kansas City chapter of the NAACP, and he joined forces with Franklin’s wife, Ada Crogman Franklin, to convince Franklin to report on politics and serious issues. Wilkins left The Call in 1931 to become assistant secretary of the NAACP in New York, and Bluford replaced him as news editor when she began working full time for the newspaper in 1932 after she graduated from KU.

Despite his conservative reputation and penchant for profit, as editor and publisher of The Call, Franklin endorsed the progressive statement that appeared on the editorial page in 1936: “The Call believes that America can best lead the world away from racial and national antagonisms when it accords to every man, regardless of race, color, or creed, his human and legal rights. Hating no man, fearing no man. The Call strives to help every man in the firm belief that all are hurt as long as anyone is held back.” The use of “man” in the statement was standard for the day, but ironic given that Bluford, a woman, would soon lead the way for legal rights. Gender may have been an asset to Bluford’s campaign, as historians speculate that she may have thought that it would be safer for a woman than a man to challenge MU. Given the fact that African American women frequently were the victims of white violence, however, this point is debatable—and in any event, it cannot be confirmed by the many sources that I have consulted.

Despite speculation at the time and in subsequent scholarship, Bluford acted on her own in applying to MU and was not a pawn of the NAACP, according to court records and other evidence. Bluford sent her application in early January 1939 and was provisionally admitted because the registrar did not know that she was African American. On January 30, 1939, Bluford arrived on campus and then recounted her experience for The Call on February 3, 1939. She reported, “After spending two hours on the M.U. campus as a prospective student, I am thoroughly convinced that the students are not perturbed over a Negro’s entrance. I found the students no different from that at K.U. [University of Kansas], where I was a student for four years. Some are friendly, most of them indifferent. I found no animosity.” Bluford described her meeting with the dean of the MU School of Journalism, who told her that she had the prerequisites to begin a master’s program but lacked permission to enroll in classes. She then noted that the registrar’s office refused to grant her permission to register for classes.

Bluford also informed readers that she spoke to several white journalism students and a white faculty member. The students and instructor did not object to her efforts to enroll, according to Bluford, and one student told her that he regularly read The Call, which he described as “the best weekly in the state.” Using these sources to support her argument that there would not be “trouble” if an African American student went to MU, Bluford provided reasons for her actions:

After being "in the field" for five years, I think it time to "brush up" in my profession. That’s why I planned to return to school. My logical choice is M.U. Missouri has the strongest school of journalism in the country. It was the first established in the United States. Students come from all over the world to study journalism in Missouri. While I was waiting in the registrar's office, I saw students from many foreign countries receive their permits to enroll. There was one boy from Portugal who wanted to study journalism. He was admitted.

Bluford then cited statistics about the MU student body, observing that students from 11 different countries, every state of the United States, and every county in Missouri attended MU. She concluded matter-of-factly: “They come from everywhere to Missouri U. I live in Missouri.” Compiling a remarkable collection of evidence, Bluford and The Call tried to convince readers that African Americans could challenge segregated education.

By quoting the white student who praised The Call, Bluford suggested that whites also read the publication. In 1939, The Call had 19,020 subscribers and published different editions that reached readers in Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming. Readers included African Americans who supported the campaign for educational equality; African Americans who supported racial justice initiatives, but did not always agree about the best way to challenge discrimination; and African Americans who did not regard themselves as part of an African American social justice movement. Although it is impossible to determine how many whites read The Call in 1939, it is probable that some did. In his autobiography, Roy Wilkins reported that by 1931, the circulation of The Call was 20,000 copies a week. Since there were only about 14,000 black families in Kansas City at that time, the newspaper must have reached every black household and white readers as well, according to Wilkins.

During her testimony at a hearing in the Boone County Circuit Court in February 1940, Bluford claimed that The Call had “a large number of white readers” that included subscribers and Kansas City reporters for other newspapers, as well as social workers, members of juvenile court staffs, and “persons interested in learning the problems of the whole community.” Among these white readers, it is likely that some were sympathetic to the African American campaign for equal education, such as the students and faculty whom Bluford met at MU, and some opposed or ignored the campaign. The front-page placement of Bluford’s first-person stories and the scope of the coverage of her experience at MU signals that The Call intended to persuade all readers that change was possible.

Definitively characterizing the audience of The Call in the 1930s before the advent of sophisticated market analysis is challenging. Economist and sociologist Gunnar Myrdal asserted that the majority of African American readers of black newspapers in the mid-twentieth century were members of the middle class and “the upper layers of the lower class” in his landmark study, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944). Myrdal defines the “Negro press” of this era as “a fighting press,” “an educational agency,” and “a power agency,” and noted that upper-class African Americans wrote and published newspapers to influence the opinions of lower-class blacks.

Differences of African American class and the consequences of those differences for the black community of Kansas City are noted by Wilkins in his autobiography:

Deep divisions separated the town’s [African American] social classes. At the bottom was a floating world of hustlers, torpedoes, fly-by-night artists, and easy women. The center was held by solid workingmen, railroad porters, hod carriers, and truck drivers, a labor force that was far larger than anything I had seen in St. Paul. At the top was a prosperous upper middle class of doctors, lawyers, dentists, pharmacists, teachers, school principals, and a scattering of businessmen.

Referring to professional gunmen as “torpedoes,” Wilkins also alludes to his upbringing in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he lived in a racially integrated neighborhood.

What Wilkins calls the “top” of the black Kansas City community was small: historian Charles E. Coulter calculated that only 3 percent of African Americans could be classified as middle class during this time and that “the foundations for the political and economic success for black elites lay in the trials and triumphs of the black working class” that constituted the majority of the black community. Wilkins claims that most of the “elite, middle-class” African Americans with whom he associated in Kansas City were not committed to change and “were content to live with what they already had.” Frustrated by what he perceived to be widespread African American acceptance of Jim Crow codes and the low status quo of blacks in Kansas City among all classes, Wilkins proved the power of the black press in small ways. For example, in 1930 he organized and publicized in The Call a boycott of a white-owned local bakery that depended on black consumers but refused to hire black truck drivers; black shoppers responded by refusing to buy the bakery’s bread, and the company was forced to employ Negro drivers. Wilkins and Coulter attest to the fact that there were divisions in the African American community that challenged blacks who wanted to inspire change and collective action.

Nine years later, Bluford and The Call tried to inspire change and collective action by appealing to different audiences of the newspaper, including African Americans who questioned the emphasis on education by black elites. This group of readers was represented by D.A. Holmes, a prominent African American minister in Kansas City, shortly after The Call began to cover the Gaines case. In “An Open Letter to The Call,” published in the city edition on February 21, 1936, Holmes wrote:

In Kansas City, the Negro needs everything, “from the hat down and from the overcoat in,” as the song expresses it. Rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief are making a clamor for what they want. Why shall not we? Negro citizens in our home town ought to at least tell what they want. That I am endeavoring to do Mr. Editor, both to get an outlet for my pent-up feelings and to make all of your readers think about what they need.

Holmes continued by citing the poor lighting and damaged sidewalks and roads in African American neighborhoods and business districts, comparing the condition of these areas to the well-maintained Country Club Plaza and other areas for whites. Complaining that there was no public meeting place for African Americans nor effective representation on the Kansas City council, Holmes then posed a provocative question: “What’s the use of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People coming to Missouri to fight in the courts for equal education when death-dealing unsanitary buildings, expressing only landlord greed, are allowed to stand?” Although Holmes was active in the Kansas City chapter of the NAACP in the 1920s and 1930s, he took issue with the focus of the NAACP on education during the deprivations of the Depression, which exacerbated racial inequities in Kansas City.

To accommodate readers who believed that addressing the economic plight of African Americans during the Depression was more important than advocating the integration of public universities, Bluford and The Call used the account of her trip to MU to encourage blacks to redefine themselves. Whereas Holmes defined African Americans as victims of whites, Bluford defined herself as a rational and qualified applicant pursuing her right to equal education. For example, in her second first-person story, “Missouri U. Not Ready for Negro,” Bluford calmly narrated her experience at the registrar’s office: “The University of Missouri found a loop-hole Monday to prevent me from enrolling in the school of journalism for graduate work. A week before I came to Columbia, my credits from the University of Kansas, where I received my A.B. degree in journalism, had been accepted and the registrar had told me by letter that my credits were sufficient for admittance to the graduate school. He sent me a registration blank and told me to come by his office when I arrived in Columbia to receive my permit to enroll.” To prove her point, Bluford then quoted from the registrar’s letter before resuming her account. Instructed to stand in line for her permit, she claimed:

When I joined the line, there was not a ruffle of excitement. Students who came in the office after I did stood behind me waiting their turn, paying no more attention to me than they would any other new student enrolling. No one in the line said anything to me. There were no comments about my presence, no demeaning glances at one another. The students chatted about “dates” and the courses they planned to take.

Continuing the account, Bluford reported that a secretary escorted her to the registrar’s office, where Canada read a prepared statement from the MU Board of Regents that indicated the university was contesting the decision of the Supreme Court on the Gaines case. “After hearing this statement, I asked Mr. Canada how the Gaines case could go back to the Missouri supreme court after the United States supreme court already had ruled on it. He said, ‘I really don’t know. I’m not a lawyer and am not familiar with all the legal angles.’” Rather than chastise Canada in print for his remark, Bluford concluded this first-person story by noting that she and the registrar “chatted for a quite a while” and he suggested that “the matter” might be straightened out by September and then she could then enroll at MU. Ending on an optimistic note, Bluford implied that her efforts were not necessarily in vain.

Of course, the matter of Bluford’s admittance to MU was not straightened out by September 1939, and she repeatedly tried to enroll at MU while her NAACP lawyers pursued legal action through the early 1940s. The Call continued to confront readers by reporting on Bluford’s court appearances, responses by MU, and the efforts of the Missouri legislature to circumvent the Supreme Court ruling.

Bluford did not, however, write any more first-person stories until May 1, 1942, after she lost her second civil damage suit against the MU registrar. That day, The Call published her column, “How I Feel About Missouri U. Case,” on the front page. Seeking to stir both sympathetic and resistant readers, Bluford declared:

The most brazen, impassioned appeal to race prejudice that I have ever heard was made by William S. Hogsett, attorney for the University of Missouri in my damage suit against the university registrar tried in federal court at Jefferson City last Thursday and Friday. “We speak Anglo-Saxon,” he bellowed in his closing argument to the 12 white Missourians on the jury. “We understand each other. If this colored girl wants to study journalism let her go to Kansas.” Hogsett, a reputable Kansas City lawyer, knew in his heart that he had lost the case. The law and the facts were clearly against him and in our favor. In dignity of presentation, eloquence of expression, brilliance of mind, and depth of soul, Hogsett was overshadowed by our lawyer, Charles H. Houston, who came from Washington to prosecute the case. Thus defeated, Hogsett then took the only course open to him—a direct plea to the jury to act as white men and put in her place a Negro who dared sue the state for her rights as a Missouri citizen.

Positioning herself again as a reasonable person, Bluford encouraged readers to judge rather than merely accept Hogsett’s racist tactics and arguments.

A week later, Chester Franklin confronted readers about Bluford’s case. In an editorial published on the front page of The Call, Franklin wrote:

To every Public-Spirited Negro Citizen of Missouri, especially to Ministers, Teachers, and CALL agents. Dear Fellow Missourians: The outrageous verdict in the Bluford case, tried in the federal court in Jefferson City on April 23 and 24, is a blow to Negro education everywhere in Missouri . . . We must not let the Bluford case be the end of our fight for equal education . . . To raise a “FIGHT FOR JUSTICE” fund, I am giving the first $1 and have deposited it in the People’s Finance Corporation of Kansas City. I call upon you to help raise the $2,000 needed. What I ask of you, you can do quickly. Tell of this need to everybody in your community. Tell them all. Methodists and Baptists, Republicans and Democrats. Tell white people who believe in fair play. The important thing is not how much each gives but that this appeal represent[s] all of us. No one person gives a large amount. Let everybody give.

Vowing to print the names and hometowns of contributors in the newspaper, Franklin urged readers to think of themselves as active agents of change, not passive spectators of racial injustice, and to recruit whites to a new phase of the persistent protest for African American rights. Seeking to appeal to audiences with varying priorities, he linked equal education to the broader concept of “justice.”

Fifteen years after Bluford and The Call began to collaborate to pursue equal education for African Americans, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racially segregated education in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (1954). In 1955, Franklin died, and Bluford became editor of The Call. She and the newspaper continued to address issues of racial justice, such as the Kansas City department store diner boycott in 1959. In 1989, 50 years after Bluford tried to enroll at MU, the university awarded her an honorary doctorate. Bluford accepted the degree “not only for myself, but for the thousands of black students” that the MU had barred for years. Although Bluford was known as the “conscience” of Kansas City until her death in 2003, her historic collaboration with The Call in 1939 to promote the persistent protest for African American rights has not been acknowledged. Unlike some more famous African American women journalists, such as Ida B. Wells, Bluford did not write an autobiography that might have set the record straight. Rather she let the facts, as she documented in her first-person accounts for The Call, speak for themselves. A middle-class, well-educated activist who was part of what Gunnar Myrdal identified as the “fighting press,” she capitalized on her skills and access to the persuasive forum of The Call to challenge the complacency of blacks and whites in Kansas City. Although Bluford failed to cross the MU color line, she continued to confront readers to stand and speak up for racial justice throughout her 69-year-career at The Call.

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.