The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Kansas City

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, and was ratified and became law on August 18, 1920. This amendment granted voting rights to, in theory, all women in the United States. But the push for women’s suffrage was not solely a northeastern or coastal interest. It was fueled by individuals and organizations across the United States, with many states passing suffrage prior to the 19th Amendment.

Midwestern states have historically been major sites in the complex history of enfranchisement. Kansas briefly showed promise for suffragists in the Civil War era. A stronghold for abolitionists, the fledgling state considered suffrage for both women and African Americans. The state’s constitution that went into effect in 1861 allowed women to vote in school board elections, property rights, and equal custody of their children, but it stopped short of full suffrage. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s History of Woman Suffrage captured the opportunity that Kansas seemed to present: “There never was a more hopeful interest concentrated on the legislation of any single State, than when Kansas submitted the two propositions to her people to take the words ‘white’ and ‘male’ from her Constitution.” Kansas, however, followed national trends on the matter of women’s suffrage ; as described by Stanton and in a 1975 dissertation by Sandra Madsen, Republican reformers of the post-Civil War era deemed women’s suffrage a lower priority than black male suffrage and citizenship rights.

Missouri’s voting rights history was contentious from its inception in 1821, when women’s voting rights were far from serious consideration; rather, the Missouri statehood debate centered on its status as a free or slave state. Even after the Civil War and the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, black male voting rights were anything but assured in Missouri. John McKerley elaborates on the struggle over black voting rights:

In Missouri, as in many former slave states, the federal enfranchisement of black men kicked off a period of unprecedented black political involvement. Unfortunately, it was also brief, with Missouri Democrats taking advantage of white resistance to black voting rights and briefly joining with a breakaway group of Liberal Republicans, who opposed racial restrictions on black men’s voting rights but also resisted aggressive means to use state power to safeguard the rights of black people generally. In less than a year after black men in Missouri gained the right to vote, the two groups had combined to remove Radical Republicans from office, setting up decades of statewide political dominance by Democrats.

Consequently, the Missouri women’s suffrage movement was always part of a larger conversation surrounding representation, race, and citizenship in the United States. At the same time, midwestern territories were, in some cases, among the first to grant women voting rights and other political freedoms. Wyoming Territory, for example, was the first to offer women’s suffrage in 1869. Kansas women finally gained full suffrage in 1912, and Missouri women did not gain the vote until the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

With its location on the Missouri-Kansas border, Kansas City is a particularly interesting case study in voting rights history and is inseparable from broader national developments.

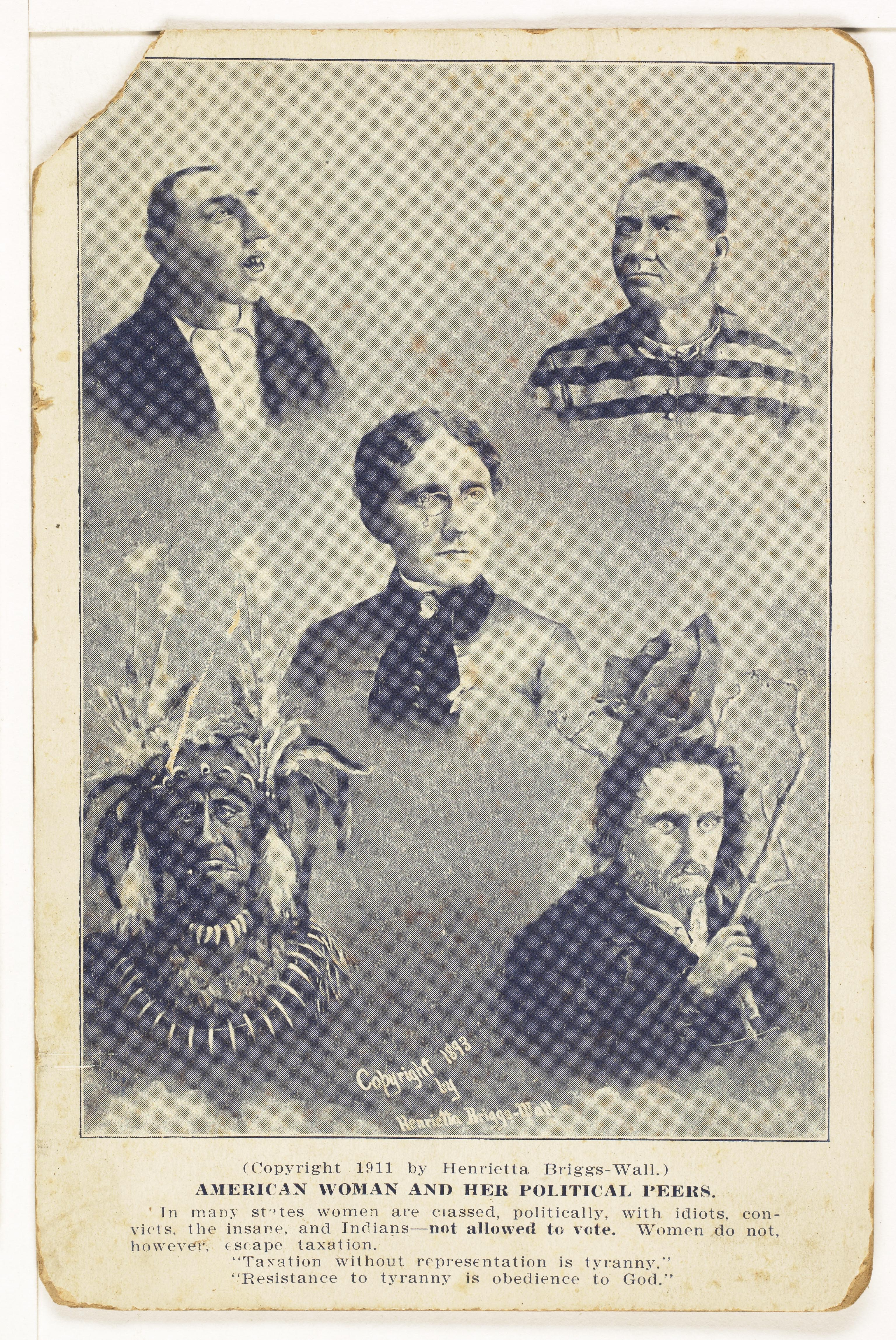

Though many women’s suffragists were also abolitionists and, later, participants in maternalistic "racial uplift" projects, the women’s suffrage movement also often relied on appeals to white supremacy, patriarchal standards of ideal white womanhood, and wartime patriotism to achieve their ends. This complicated history of an important progressive movement in United States history is documented in histories, newspapers, club memos, and organizational publications and magazines.

National and Local Suffragist Organizations in Kansas City

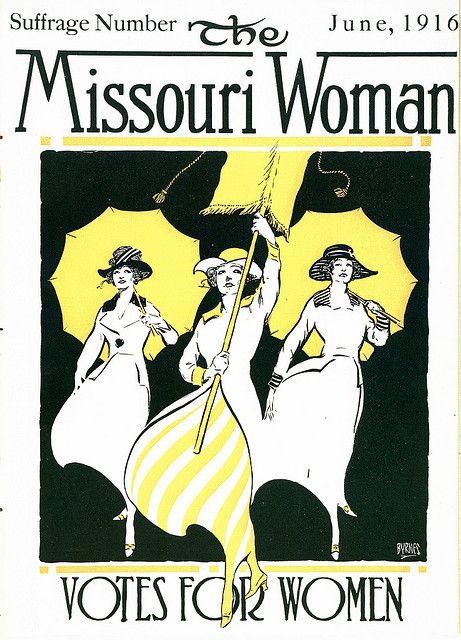

One such publication was the Missouri Woman, the "official organ of the Suffrage movement." Publications like this gave women a communication platform to discuss everything from matters related to the war, social opportunities, global politics, and theoretical considerations. Lucille Lowenstein’s January 1919 article asked, for example, "Have women a group consciousness?" It addressed important issues specific to women, like the fear of unemployment after soldiers returned home from war. It also gave women a rare venue to voice and debate their political opinions (a February 1919 article is headlined, “Does Mr. Reed Think?” in reference to anti-suffrage Missouri state senator James A. Reed). Most importantly, this publication allowed for the spread of news to Missouri women regarding the women’s suffrage movement locally and nationally. Because of the development of a new leisure economy, promptly followed by the wartime influx of women into traditionally male workplaces, urban spaces in particular became hubs of homosocial activities and impressed upon the country a new view of women’s capabilities and potential place in American society. These organizations began working towards the suffrage initiative, and Kansas City was a central site of this type of women’s club activity.

In December 1915, the Missouri Woman documented a meeting of the Political Equality League in Kansas City where an open meeting was scheduled at the Carleton Hotel. This type of public meeting is a telling choice, as open meetings were farther-reaching activities than more exclusive club events. And, with speakers scheduled from as far as New York, these types of events represented the suffrage movement’s influence on club life from narrow social pursuits to political engagement at a national level.

Other meetings, bazaars, and “fellowships” were also announced. In the February 1916 issue, the Political Equality League reported their election results, and the Central Suffrage Association, led at the time by Phoebe Ess, announced the signature gathering activity in Jackson County, as well as the efforts of their Literature Committee in gathering suffrage-related articles and books for a local high school. The article “Jackson County to the Fore,” reports on the activities of several of Kansas City’s women’s suffrage organizations. An April 1919 report on suffrage activities described how members of the Jackson County Equal Suffrage Association had “done fine work for the cause during the past eight months . . . [circulating] petitions and, in spite of the heat and later the influenza epidemic, [securing] the signatures of 40,095 people who were in favor of suffrage.” In addition to these more stoic reports of club activity, the Missouri Woman often featured colorful arguments defending suffrage, including a 1919 article, “Forceful Mating,” that quipped: “the vote will not satisfy the need of women for men any more than it seems to have satisfied the need of men for women.”

Prominent Women Suffragists of Kansas City

Suffragist women risked their reputations and, often, their well-being when fighting for the right to vote or otherwise engage in political life. The 19th Amendment was finally won because of the persistent, collective effort by ordinary women across local, state, and national organizations. Several of these women stood out in Kansas City as distinguished leaders in the women’s suffrage movement:

Sarah Chandler Coates"There should be no discrimination made between the sexes as regards the privilege of the ballot; I am opposed to class legislation." Though it reads as mild-mannered today, this statement by Sarah Chandler Coates was, at the time, a radical statement, especially from a white woman of status who materially benefitted from conservative politics. Though she claimed she was "never a society girl," Coates was a leader in women’s club life. She focused these efforts on political and moral pursuits rather than social ones, however, and became a significant leader in the women’s suffrage movement locally and nationally. Historian Barbara Magerl describes Coates as a "cultural and civic force," who "shocked family and friends by studying human physiology."

It was Coates’s access and commitment to her academic and religious education that laid the foundation for her future convictions and political involvement. Coates was born in Pennsylvania on March 10, 1829, to Quaker parents. She attended seminary, became a teacher, and went on to help found a Unitarian church. Her education pursuits and experience in religious spaces that permitted women’s involvement undoubtedly influenced her views as a women’s suffragist.

Coates moved to Kansas City, Missouri, permanently in 1859 with her husband, Colonel Kersey Coates, a lawyer who fought for the Union army. Her three children compiled a history about her life, edited by her daughter Laura Coates Reed, which they published in 1898. They documented her many accomplishments and involvements in Kansas City. For example, they described how Coates was an abolitionist and criticized the United States flag for “speaking of freedom” hypocritically. They also describe her commitment to the education of her “dusky friends,” referring to her decision to teach black children and adults. The text also documents part of a letter from Susan B. Anthony to Coates, who had visited her several times in Kansas City, discussing women’s suffrage. After a lifetime of political activism and women’s club activism, Coates died on July 25, 1897.

Phoebe Jane Routt Ess

Phoebe Jane Routt Ess was born on March 3, 1850, in Versailles, Kentucky. Her family moved West soon after, settling in Kansas City in 1972. Like Coates, Ess attended seminary and became a teacher. She was a leading woman Democrat and an incredibly active club woman in Kansas City. She held numerous leadership roles in political and charitable organizations. Celebrating the 75th Anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment, the Jackson County Historical Society Journal published in its Fall 1995 volume, "The Diamond Jubilee of the Nineteenth Amendment." The article praises Phoebe Ess’s contribution to the suffrage movement. It discusses her club involvement and immense contributions to the suffrage movement in and around Kansas City. Ess was a founding member of the General Federation of Women’s Club in 1889. She was also an officer in the Kansas City Athenaeum and served as founding president of the Susan B. Anthony Civic Club for 23 years. In addition to her efforts towards the suffrage movement, Ess was involved in prison reform and charities for widows and children. Like many suffragists, Ess was also a prohibitionist. Ess died on April 10, 1934.

Mathilde (Dolly) Dallmeyer Shelden was born in Jefferson City on December 6, 1885. She attended seminary in Washington D.C., where she first discovered women’s social and political club opportunities. She would bring what she learned back to Missouri, becoming a leading Republican suffragist in the area. She organized the Jefferson City Equal Suffrage League and was a member of the Kansas City Athenaeum and the Women’s City Club. She was also involved in other philanthropic and social clubs, serving as the president of the Jefferson City Art Club from 1906-1915. She was an activist with “great passion and dedication,” campaigning in over 20 counties and pushing the issue of suffrage at a time when women traveling so freely and for such purposes was not considered appropriate. During Sheldon’s travels for campaign speeches, Flynn describes the resistance she encountered: “so controversial was the prospect of women voting that several times she and her chaperone were refused accommodations.” In 1919, Shelden became the first woman in Missouri to hold a political office and, following the passage of the 19th Amendment, would remain involved in politics throughout her life. Most notably, Shelden was elected to the city council in 1924. She died at the age of 95 on January 17, 1980.

The 19th Amendment Becomes Law

The United States House of Representatives passed the Federal Suffrage Amendment on May 21, 1919. The Missouri Woman announced in its June 1919 issue: “Hallelujah! As we go to press the news that women have longed to hear for forty years has come—the passage of the Federal Suffrage Amendment by the United States Senate . . . there is no doubt that the Missouri Legislature will be among the first [to] ratify the federal amendment.” They were right. After proceedings that began on July 1, 1919, the Missouri legislature ratified the amendment at a 10 a.m. meeting on July 3, 1919, with “the largest delegation of suffragists that has ever attended a state function” in attendance, all dressed in “suffrage yellow.” Just a few months would pass before Tennessee would ratify the amendment, providing the last vote needed to solidify women’s enfranchisement nationally.

"Suffrage Now is a Law," the Kansas City Star declared on September 1, 1920. The announcement that Secretary of State Colby had signed the bill described how members of the National Woman’s Party, who had waited at the state department in Tennessee, “cheered” and went back to their headquarters to "plan an independent jubilation." The Star and several major national newspapers quoted no women, but did quote Colby:

I congratulate the women of the country upon the successful culmination of their efforts, which have been sustained in the face of many discouragements and which have now conducted them to the achievement of that great object. The day marks the day of the opening of a great and new era in the political life of the nation. I confidently believe that every salutary, forward and upward force in our public life will receive fresh vigor and re-enforcement from the enfranchisement of the women of the country.

Following the passage of the 19th Amendment, the Star organized a “Women’s Question Department” and began fielding questions in a special column called, “The Women Ask.” The questions and responses in this column reflect the interest in and controversies surrounding the newly acquired political rights of women and their potential limitations. Women asked what they should know before voting and were instructed to be aware of local and national issues, as well as “general merits of the candidates.” (It also interestingly mentions that people who were in “poorhouses,” or anyone who was wagering a bet on the election’s outcome, were not allowed to register as voters). Women also asked about whether they could vote on U.S. entry into the League of Nations, how to vote if they were “invalids” and unable to get to the polls, and whether they could now serve on a jury. (To the last question, in Kansas, “yes,” but in Missouri, “no.” Only male taxpayers could serve on juries in Missouri at the time, a stipulation that limited jury pools largely to white men).

Women’s clubs and suffrage-oriented organizations did not dissipate following the passage of the 19th Amendment. Social and political clubs continued to be popular, and suffrage clubs focused their attention on registering and educating women voters, as well as lobbying for other political and social reforms. Voter registration drives began, and “citizen schools” formed. Women from across the region signed up en masse to learn about the functions of government and political history in St. Louis and Kansas City.

The 1919 passage of the 19th Amendment was a hard-won and monumental moment of social progress. It set the precedent for future enfranchisement fights and the feminism movements later in the century. The organizational capacity and subsequent victories of the suffragist movement in places like Kansas City were the result of an inordinate amount of strategic effort, especially considering the distractions of war and the flagrant political and business corruption undermining the rights of so many during this time. It is imperative to remember, however, that while legally both black men and women had the right to vote after the passing of the 19th Amendment, this was largely not a material reality until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This act also strengthened the voting rights of Native Americans, rights which had not been recognized by all states until 1962.

This essay was developed as part of an Applied Humanities Summer Fellowship, cosponsored by the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas. Additional support from the Missouri Humanities Council.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.