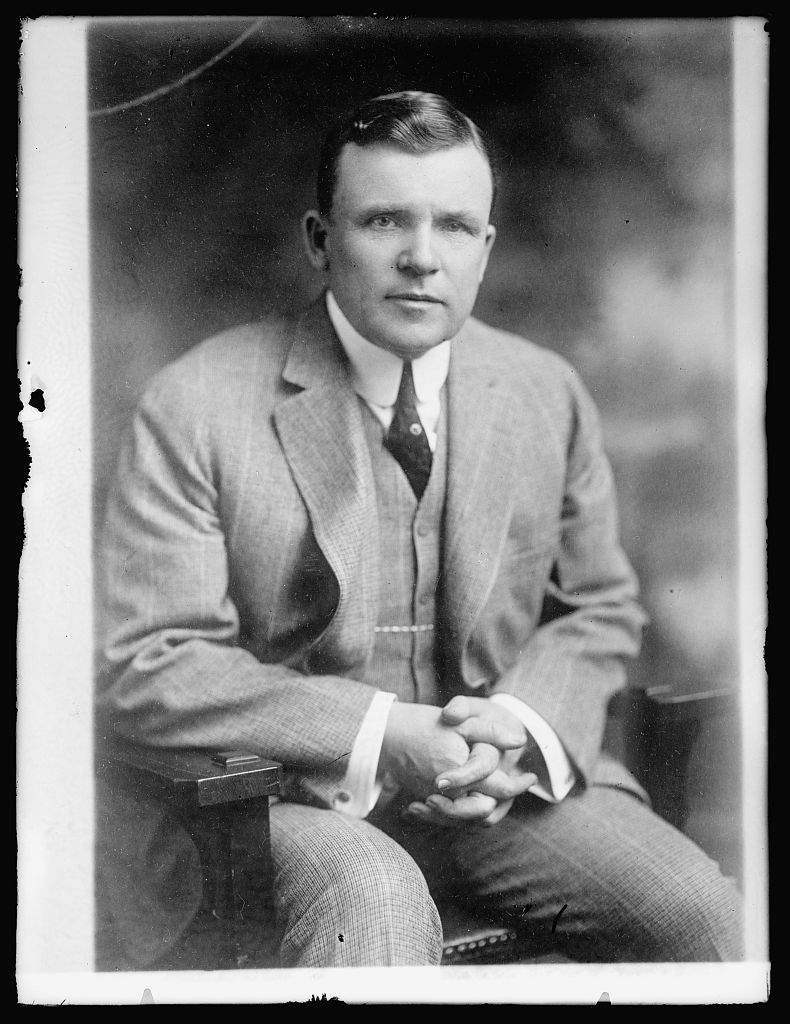

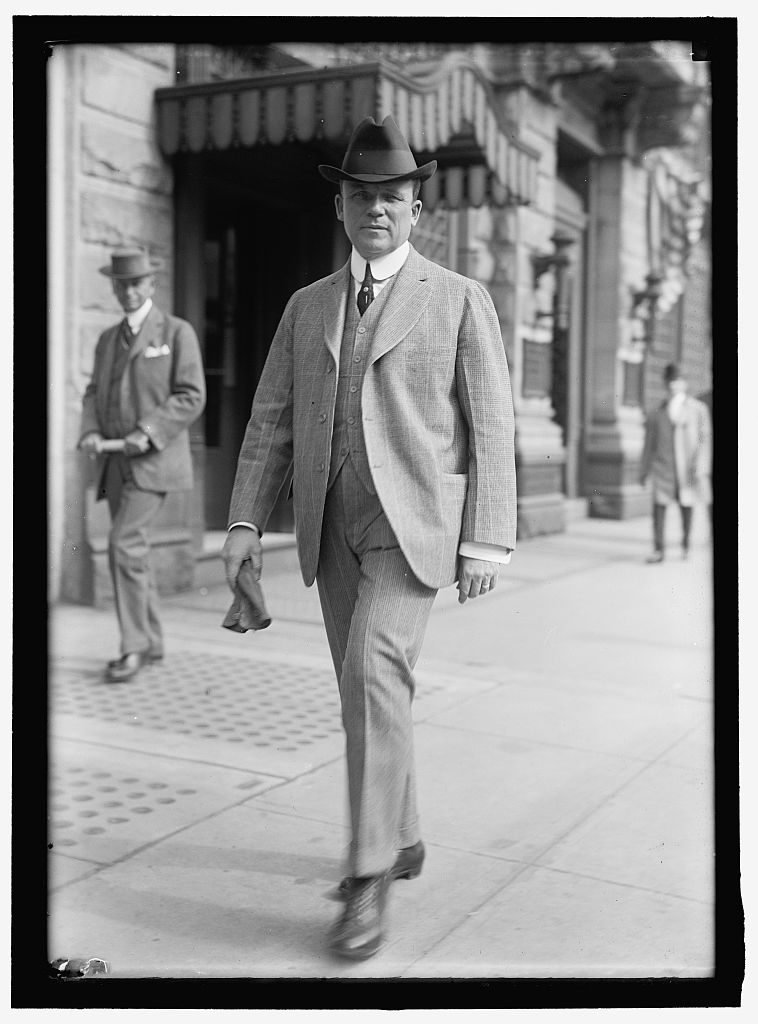

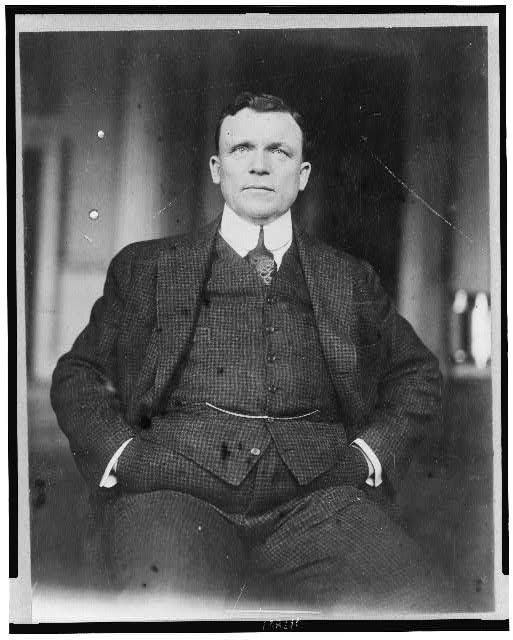

Frank P. Walsh

- Also Known As: Francis Patrick Walsh, Frank Walsh

- Date of Birth: July 20, 1864

- Place of Birth: St. Louis, Missouri

- Home: Kansas City, Missouri

- Spouse: Katherine M. O’Flaherty

- Date of Death: May 2, 1939

- Final Resting Place: Mount Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Kansas City, MO

Frank P. Walsh was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1864 to James and Sarah Walsh. A progressive lawyer and labor advocate, Walsh was committed to workers’ rights, public welfare, and “clean” government. His standoffs with Kansas City Mayor and U.S. Senator James A. Reed were particularly famous because both men were passionate and skilled orators on far opposite ends of the political spectrum. Walsh was a controversial figure during a time of rapid industrial expansion in the United States. He was criticized for elaborating his rags-to-riches upbringing and, more seriously, for his infringement on the accumulation of wealth by unchecked business pursuits at the expense of working-class livelihood. Walsh’s views of shared wealth, combined with his skill as a litigator, equipped him for prominent positions in the New Deal era. Described as an “agitator” and a radical, Walsh believed a country that was rapidly accumulating wealth should have higher standards of living for its citizens than primitive food and shelter.

Though many critiqued him for exaggerating his childhood hardships, Walsh did face some challenges and limitations at an early age. George Creel and John Slaven’s 1902 compilation, Men Who are Making Kansas City, describes Walsh as an “attractive and forcible public speaker” who left school very early and “now ranks at the head of the Missouri bar.” Walsh left school at the age of 10 after attending the Christian Brother Academy for several years. He would later attend a St. Louis public night school. He worked as a messenger for Western Union Telegraph Company, a clerk and, later, a cashier at St. Louis and Cairo Railway Company, and then a talented stenographer at the Lathrop and Smith law office.

It was his time at Lathrop and Smith that inspired Walsh to pursue a career in law. He was admitted to the bar on November 1, 1889. He set up his first practice, Douglas and Walsh, in Kansas City and there married Katherine M. O’Flaherty in 1891. The 1901 Encyclopedia of the History of Missouri details Walsh’s career path to becoming a successful lawyer. Describing Walsh as “an uncompromising Democrat” and a “forceful and impassioned orator” the biography anticipated the success of Walsh’s career after the turn of the century: “His studies have afforded him deep knowledge of the law, and his well-disciplined mind is amply equipped for thorough exposition of his case, particularly through the medium of cross-examination, in which he is exhaustingly searching.” Walsh dissolved his first practice when he was appointed assistant city counselor, a position in which he served three successful terms. He later established the Rozelle and Walsh practice.

One of Walsh’s most famous cases was State of Missouri v. Jesse E. James. In 1889, Walsh defended James, son of the infamous Jesse James, who pled not guilty in a train robbery. Senator James A. Reed was the plaintiff’s attorney, and this case was one of two Reed would lose in his entire career. Though the judge made it clear he believed James guilty, Walsh’s convincing argument and wealth of evidence in James’s favor made it impossible to find him legally guilty. James was ultimately acquitted, and Walsh encouraged him to pursue a career in law.

Under Walsh’s mentorship, James worked in Kansas City, often defended workers’ rights, and sued railroads for employee negligence. From 1909 to 1917, Walsh defended Dr. Hyde in State of Missouri v. Dr. Bennett Clark Hyde. He faced off again with Reed and tried to prove Dr. Hyde innocent in the murder of Thomas H. Swope and 11 other relatives in order to enlarge his wife’s, Francis Swope Hyde’s, inheritance of the Swope fortune. Thomas Swope was a wealthy investor and philanthropist, widely beloved by the public. An autopsy revealed traces of poison in Swope’s body, yet investigators confirmed that the relatives all died in an outbreak of typhoid fever. Dr. Hyde treated all of them during their respective illnesses, though he claimed Swope had suffered and been treated for a stroke. Reed provided a wealth of evidence against Dr. Hyde, proving he had purchased cyanide capsules and typhoid cultures. After three agonizing trials, each attracting widespread public attention, Dr. Hyde was convicted. However, Walsh succeeded in having the trial declared a mistrial and the guilty verdict dismissed. The cause of Swope’s death was left, technically, a mystery. Swope was buried in a large memorial in Swope Park, a large tract of land he had donated to the city in 1896. Francis Swope Hyde divorced Dr. Hyde, leaving him financially unstable for the rest of his life. He died of a stroke in 1934.

Walsh’s efforts in Kansas City reflected a commitment to curtailing the power and influence of the Pendergast machine. Harry Haskell’s Boss Busters and Sin Hounds: Kansas City and Its Star describes Walsh and many of his involvements in Kansas City and his controversial connection to the Star. Walsh served on the Board of Public Welfare, the first such program in the country. In 1912 the board issued a report that revealed, with some analysis, the poor conditions of the city. Though Haskell relegates the board to “the mongrel brainchild of a German businessman, a Russian social worker, and an Irish lawyer,” wherein Walsh “paraded his radicalism and Catholicism,” the board’s studies attended to issues of public concern not previously addressed by a government board (as opposed to private charities). Most notably, the report discussed the slew of homes without running water and widespread unsanitary conditions, even as new developments with middle and upper-class homes introduced improvements and luxuries.

Walsh also served on the Kansas City Tenement Commission, the Board of Civil Service, and was a leader of the People’s Lobby. His work as a lawyer and political figure in Kansas City threatened many of the interests and sensibilities of powerful people in the area. In 1896 Walsh was retained by the Metropolitan Street Railway Company of Kansas City. In an August 1909 article in The National Motorman and Conductor, Bernard Corrigan (a former streetcar mogul who was then trying to obtain a private monopoly over streetcar services), criticized Walsh and the Star for hurting workers and industry, threatening the peace. Corrigan describes how Walsh’s claims were “prompted and controlled by the Kansas City Star,” which “tried in every conceivable way to incite the employees of the Metropolitan to organize a strike,” and for threatening the integrity of the men who made up the West Traffic Way Commission.

Walsh’s influence in other states and in federal government matters increased partly due to his skill but also as a result of timely social and political conditions. Labor organizations and radical individuals sought his support and expertise as he proved a skilled and generous advocate for people of controversial political stances and low social standing. He defended radicals, communists, and anarchists, notably participating in the court case of the Italian anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti. Walsh represented the miners in the Mingo Coal Strike and the Railway employee’s department. In Cleveland, Ohio, Walsh defended the female street conductress union when the male streetcar conductor union demanded they be fired. He protested to the National War Labor Board on their behalf. They won the case, but the ruling was never enforced.

In 1918 Walsh represented the Chicago Stockyard workers during an arbitration hearing ordered by President Woodrow Wilson. In an April 1918 edition of Hellraisers Journal, William Z. Foster, the secretary of the Chicago Stockyards Labor Council, wrote about the workers’ demands for higher wages, better conditions, and an eight-hour workday. Foster reflected: “Just how far-reaching will be the results of the decision one cannot now forecast. But lips stiffened by poverty will perhaps now learn to smile, and thousands of families will for the first time taste of life.” He reported that the packers wanted to destroy the unions and how the union’s demands were deemed inappropriate during the war. The union had asked President Wilson to seize the industry. Wilson declined to do so but did order the hearing. As Judy Ancel elaborates on the Kansas City Labor History Tour:

The case drew nationwide attention as a test of wartime no‐strike pledges by unions. The packinghouse unions were demanding a living wage, the 8-hour day and the right to union membership. . . . Walsh's final summation was an 8-hour discussion of the wage and hour dispute. During it he lost his voice but continued by whispering in the Judge's ear. After their victory, the union assessed each member $1 to pay Walsh, but he refused the money.

Following Walsh’s success, Foster stated: “The bringing about of these revolutionary changes constitutes one of the greatest achievements of the Trade Union movement in recent years.”

Walsh was increasingly involved in federal government committees and advisory boards. The Act of August 23, 1912, created the United States Commission on Industrial Relations for the purpose of investigating the cause and issue of labor unrest. President Woodrow Wilson appointed Walsh as chairman of the commission, a position he held from 1913 to 1915. One of Walsh’s most notable influences during the Commission’s research was his relentless investigation of the Rockefeller Foundation, partly in response to the Ludlow Massacre on April 20, 1914. Though Rockefeller tried to convince the public and commission that he was compassionate and unaware of problems related to his workers, Walsh was not convinced. He subpoenaed Rockefeller’s correspondence and exposed Rockefeller’s animosity towards workers, unwillingness to recognize the United Mine Workers Union, knowledge of poor conditions, and efforts to cover up crises with extensive public relations intervention. Walsh did not mince words in his critique:

Wherever there is a big Rockefeller interest, there you find brutal slave driving methods in the treatment of underpaid workers. . . . The most dangerous as well as brutal feature of the Rockefeller treatment of labor, is the close control that the Rockefeller concerns gain over the police and other public authorities. With the mayor of Bayonne confessing that he is a hired attorney for the Rockefeller interests, and with the police department using its full force, and hundreds of special deputies [derided by unionists as company “gunthugs”] to beat and kill the revolting strikers, the American public has its latest demonstration of what Rockefellerism means.

The commission’s final report and testimony was submitted to Congress in 1916. Walsh’s values are strongly reflected in this document, having ensured half of the representatives on the commission were representatives of organized labor. Though littered with xenophobia, particularly anti-Chinese sentiments, and posing women and children’s labor as a threat to fair competition between white male workers for jobs and wages, the document reflects Walsh’s influences in many ways. For example, Walsh saw the law “not as an end but as a means toward a more just society.” The document, then, calls for moving “beyond the law” to consider ethics and real-life impacts of the choices made by national and state government regarding labor law. Walsh wrote, introducing the report: “It is believed that the work of the commission has been conducted in a spirit of social justice and an earnest desire to serve the public by bringing into the light the facts regarding the industrial relations of the country.” This spirit manifests itself in a few areas of the report. For example, it emphasizes the “[lack] of democracy under scientific management,” as well as the difficulties and injustices workers faced under a system that was established and measured by their bosses (and consequently privileged employers’ voices and desires).

Walsh’s father, James, was an Irish immigrant, heritage that would prove to be an immense influence on Walsh’s political career as an anti-imperialist and advocate for Irish liberation. He became widely known as the “leading American Spokesman for Irish independence.” Joe Popper reported in Star Magazine’s “The Greatest: Remember Frank Walsh, Attorney at Law,” how Walsh hosted Earron De Valera, the “hero of the movement for Irish independence, prime minister of the Irish Free State and the first president of the Irish Republic.” Walsh visited Irish political prisoners and wrote a report of English atrocities. During World War I, President Wilson appointed Walsh the co-chairman of the War Labor Board along with former President William Howard Taft. In 1928, Walsh became an advisor to then-New York governor and future President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Walsh later organized the Bureau of Social service under the Democratic National Convention to support social and economic reform legislation.

In 1937 Walsh returned to Kansas City to try what turned out to be his last case. He defended the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) against the Donnelly Garment Company. The company was suing the union and calling for an injunction, claiming infringement on business and the harassment and exploitation of workers. Walsh once again squared off against James A. Reed, who was married to the company’s owner, Nell Donnelly Reed. This time, though, Walsh lost the case., Some of their court interaction is recorded in Reed and Walsh’s examination of Elizabeth Reeves, a floor manager at the Donnelly Garment Company who allegedly permitted the harassment of unionized workers and established spy systems to mitigate union membership in the shop. Within this examination and other court documents, it is apparent that there was a fundamental difference of values and conception of the purpose of labor unions by the arguing parties. Backed by multiple detailed affidavits, Walsh tried to argue that the need for a union was not based on the kindness and disposition of a factory owner but the fundamental right of workers to have access to the means of collective bargaining made possible only by external organizing.

Reed, however, claimed that male organizers from big cities intimidated vulnerable midwestern women into joining unions. He described the company's amenities and claimed that workers were well-treated and happy and the ILGWU had invented claims of unrest. He also emphasized the infringement on interstate commerce and the high cost of production caused by strikes, boycotts, and picketing. Not only did the court grant the injunction the Donnelly Garment Company requested and heavily fined the ILGWU, but it ruled the case did not qualify as a “labor dispute.” This decision importantly abdicated the court’s and the Donnelly Garment Company’s responsibility to recognize the protections of the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932, which guaranteed, among other stipulations, that anyone involved in a labor dispute had the right to strike, join a labor organization, assist in a labor dispute related court case, or peaceably assemble, and give publicity to that labor dispute. The lack of this acknowledgment and its subsequent protections rendered any evidence the ILGWU and Walsh produced not only useless but damning.

Frank Walsh’s influence stretched across the United States and abroad throughout his career as a lawyer and political figure. His impact in Kansas City was defined by his passion for labor rights, public welfare, and a government accountable to the people. A difficult stance during a regime of rampant corruption in Kansas City, Walsh was criticized heavily and sacrificed time and effort working pro bono for many working-class individuals and organizations. Though his career took him in different directions, he always considered Kansas City his home. On May 2, 1939, Walsh died of a heart attack at the age of 75 in New York City.

This essay was developed as part of an Applied Humanities Summer Fellowship, through the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas. Sponsored by the Missouri Humanities Council.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.