The Long Struggle over Black Voting Rights and the Origins of the Pendergast Machine

One of the defining aspects of "Boss" Thomas J. Pendergast’s "machine" politics was its approach to African American voters. During the early 20th century, at a time when black people were routinely excluded from the vote by Democratic regimes in most of the former slave South, Pendergast’s Democratic organization in Kansas City succeeded in part by attracting considerable black support. While such support was not unique to Kansas City—black Missourians never lost the vote in the same way or degree as their counterparts farther South—historians often point to the city as an example of early black political realignment toward a Northern Democratic Party based in urban, industrial centers and at increasing odds with its Southern wing over the issue of civil rights.

Far from beginning with “Boss Tom,” however, this approach to black voters had a long history - longer than some historians have recognized. After the Civil War, Kansas City Democrats, like many members of their party, especially in former slave states, reorganized in opposition to black voting rights. When they failed to stop black enfranchisement (which came to Missouri through the 15th Amendment) they took a page from another group, the Liberal Republicans, who were supportive of black voting rights, at least when controlled and focused by white political leaders. Indeed, over the next several decades, both Republican and Democratic parties, especially in urban areas, adopted a “liberal” approach to black voters, appealing for black votes to win increasingly competitive elections.

At the same time, however, longstanding white resistance to black political empowerment did not go away. White political leaders and rank-and-file members resisted black empowerment through electoral politics, and supporters of black political exclusion existed along the margins, growing more powerful at the turn of the century as white Kansas Citians grew increasingly frightened and suspicious of their black neighbors. In 1908, these proponents of exclusion exploded into the mainstream, capturing Kansas City government and briefly threatening to export their revolution to the state as a whole.

Both these traditions—inclusive and exclusive—left legacies for the Pendergast machine that would emerge from Kansas City’s experiment with black disfranchisement, reinforcing the machine’s openness to black political participation without fundamentally reordering the balance of racial and political power in the city.

Race and Partisanship in Late 19th Century Kansas City

Before the Civil War, Missouri was still a slave state and restricted voting rights to white men. As the war came to an end, Missouri’s newly ascendant Republican majority (increasingly referred to as “Radicals,” especially by their opponents) began to press for greater black rights, with Democrats rallying in opposition. For example, as early as October 1865, over a hundred delegates to a meeting of Kansas City, Independence, and Westport residents declared their opposition “to negro suffrage, negro equality, miscegenation and all the kindred negroism of the Radical party.” But resistance to black enfranchisement extended to the Republican rank and file as well, with a majority of wartime “loyalists” defeating a black suffrage amendment placed on the ballot by party leaders in 1868.

In 1870, Republicans at the federal level overturned state laws prohibiting black suffrage through ratification of the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution. In Missouri, as in many former slave states, the federal enfranchisement of black men kicked off a period of unprecedented black political involvement. Unfortunately, it was also brief, with Missouri Democrats taking advantage of white resistance to black voting rights and briefly joining with a breakaway group of Liberal Republicans, who opposed racial restrictions on black men’s voting rights but also resisted aggressive means to use state power to safeguard the rights of black people generally. In less than a year after black men in Missouri gained the right to vote, the two groups had combined to remove Radical Republicans from office, setting up decades of statewide political dominance by Democrats.

In Missouri, little may have changed, with Democrats remaining the party of black exclusion, except for significant economic and demographic changes that began to transform the city and state after the war. In 1869, the Hannibal Bridge opened the city and surrounding areas to industrial development and sped Kansas City’s eclipse of competing towns along the state’s western border. Fueled by economic expansion and the corresponding demand for workers, Kansas City’s population, which stood at just over 55,000 in 1880, more than doubled by the turn of the century (eclipsing 132,000 by 1900).

Most of these new Kansas Citians were white, but a significant number of black people arrived as well. Only 190 black men and women resided in Kansas City in 1860, but over 8,100 (14 percent of the city’s total population) lived there in 1880. Although this phenomenal growth slowed over the next 10 years, the city’s black population stood at 13,700 by 1890. These black migrants represented a significant part of a larger rural-to-urban migration transforming Missouri’s black population as a whole. By 1900, Missouri had become the first state of the former slave South to have a majority (55 percent) of its black population living in cities and towns, with 70 percent of these urban black people residing in either St. Louis or Kansas City).

In this context, Missouri politicians from across the political spectrum began to reconsider their approach to black voters, especially as new migrants made urban politics more competitive. With Democrats back in power in the state and the Republican Party associated with black voting rights, Republicans (once again united) quickly began the process of appealing to the white majority, often resisting black political demands in the process. On the other hand, Democrats attempted to take advantage of black frustration by calling out alleged Republican hypocrisy and encouraging black voters to break with Republicans as a consequence.

One example of this process took place in 1888, when a black Kansas Citian, Paul Jones, attempted to win the Republican nomination for city attorney. Republicans denied him the spot, with both white and black party members arguing that running a black man for such a prominent position would repel white voters, doom the ticket as a whole, and leave black Kansas Citians at the mercy of the Democratic Party (which black people still remembered for its racism during the war years). For their part, Democrats were happy to publicize what they characterized as Republican hypocrisy and bad faith toward black voters, even while utilizing Democratic newspapers to signal the party’s commitment to white supremacy through racist depictions of black people. Jones and his supporters negotiated this difficult and dangerous political terrain by reaching out not to Democrats but to a third party—the Union Labor ticket, supported by the Knights of Labor, a working-class federation characterized by its relative willingness to organize across racial lines. Jones lost but pulled enough black support to garner more votes than any other candidate on the (otherwise white) Union Labor ticket, revealing the degree to which black Missourians had become willing and able to vote strategically.

Black Missourians had good reason to be suspicious of Democratic intentions. Even as supporters of comparative racial and political liberalism took the lead within Missouri’s Democratic Party, they never fully abandoned their willingness to use various forms of black disfranchisement to ensure that some form of white supremacy prevailed over any form of meaningful and durable black political empowerment. In April 1898, for example, the Kansas City Daily Journal reported that a black Republican, “C.A. Jackson, janitor of the Commercial Club,” was “disfranchised” by Democratic registration officials who had recorded him as having moved without reregistering at another address.

Still, over time, experiments in political independence like Jones’s candidacy in 1888 became a bridge for black Kansas Citians into the Democratic Party. Facing a political world characterized by varying degrees of white racism, black people increasingly offered electoral support to Democrats, if for no other reason than splitting their vote offered more meaningful opportunities for employment in city jobs and other forms of political influence and protection. Likewise, Democrats sought black voters to win elections. The bulk of the city’s Democrats had divided into followers of two boss factions—the “Goats,” led by James F. Pendergast, and the “Rabbits,” led by Joseph B. Shannon. As early as 1900, Kansas City Democrats and their black supporters organized a Negro Central League as part of their effort to attract black voters to the campaign of Goat mayoral candidate James Reed. After black Missourians contributed to his narrow victory, Reed attempted to consolidate some of the gains by opening jobs in the fire department and other patronage opportunities to black supporters. By 1902, when Reed ran again for mayor, his black support was so conspicuous that one white Democrat noted, “The Democratic party [in Kansas City] no longer claims to be a strictly white man’s party.”

Reinventing Black Disfranchisement in Progressive Era Kansas City

Not all Democrats were happy with boss politics. For many young men on the make, the boss system appeared corrupt and out of touch. Although various reform groups would arise to challenge the boss factions from time to time, they never came close to coalescing into anything approaching a unified “movement” until 1908, when Thomas T. Crittenden Jr. and his allies in Kansas City tried to forge one in the wake of their electoral success.

On the one hand, Crittenden might have seemed an unlikely person for such a role. He came from a distinguished Kentucky family known for its support for the status quo and the rule of law. His great uncle, John J. Crittenden, had, among many other things, authored the famous “Crittenden Compromise,” a failed proposal to avert the Civil War. Likewise, his father, Thomas T. Crittenden Sr. had moved the family to western Missouri and served on the side of the Union during the Civil War. He would later become a prominent Democratic governor from Missouri, most famous for his role in apprehending the James brothers, former pro-Confederate guerrilla fighters turned outlaws.

At the same time, however, the younger Crittenden evidenced an outspoken commitment to white supremacy and black disfranchisement. On the one hand, his political choices suggested the ways that racism undergirded the ability of white people to overcome wartime differences in the creation of postwar politics. On the other, they revealed a certain tension between those older Democrats, like his father, who had rebuilt the party amid the contested terrain of postwar politics, and those young white men like himself, who had come of age at the turn of the century. As a deputy clerk of appeals and clerk of Jackson County, Crittenden had made no secret of his efforts to exclude black men from jury service and even campaigned on the issue. “If I had the making of the law I would not have provided for Negroes serving on the juries until their education and intelligence warranted it,” he replied when pressed on black jury service by a Republican opponent. “I think it unfortunate that negroes and white people should have to serve on the same jury. I feel that, socially, the races are not equal.”

Crittenden was not alone. White Kansas Citians across the political spectrum were growing increasingly fearful of black political power. In 1905, opponents of black suffrage could point to a scandal at the city’s workhouse in which a male black guard had allegedly beaten a white female inmate. When white representatives of Kansas City’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union conducted their own study of workhouse conditions, they were appalled to find that white women sometimes bathed around black male guards and that black and white women were sometimes held in integrated cells. Another investigation revealed that a black physician employed by the city examined the workhouse’s white female inmates, leading the city council to call for the institution of segregated facilities. But when Democrats used the scandals in the mayoral election of 1906, they still went down to defeat against the Republican candidate, Henry M. Beardsley.

By 1908, therefore, when Crittenden made his run for mayor, Kansas City’s white Democrats were anxious for a return to political power and an uncontested white supremacy. Crittenden emphasized the themes of partisan unity, bi-partisanship across class lines, elevation of a new generation of Democratic leaders, and the overthrow of the Republican “machine” (a loose term used by Republicans and Democrats alike to characterize urban political organizations as corrupt and undemocratic, and defined in a variety of ways). He claimed to have withheld his nomination until he was convinced that a “united party” would back him. Finding a base of support within the Young Men’s Democratic Club, Crittenden represented the aspirations of “the brainy, brawny young men” who were “determined to aid in the overthrow of the machine.” Such young white men, he argued, included even the “best” and “taxpaying” portions of the Republican Party, who also had a stake in stopping “the extravagance and corruption that now exists at city hall.”

The Crittenden-aligned Kansas City Post first introduced race into the campaign through its efforts to link the Beardsley administration to growing white concern over crime. In late 1907 and early 1908, whites in greater Kansas City had been shocked by a series of sensationalized crimes allegedly committed by new black residents. Although some of the black men arrested in connection with the incidents confessed to the crimes, others maintained their innocence, and at least one, Grant Figgs, later recanted his confession on the grounds that he feared a “beating” at the hands of the police if he had refused.

On March 11, the Post reported that “[within] the period of seven hours a [white] woman and a little girl were assaulted by negroes in Kansas City.” According to the paper, the same black men responsible for these attacks had been brought into Kansas City, or “colonized,” by the Republicans to vote for Beardsley and other Republican candidates. While James Reed charged Beardsley with buying “nigger votes,” the Post claimed that “[evidence] is being developed daily which proves that the Republican bosses of Kansas City not only intend to buy negro votes, but that they are even now colonizing negroes for registration purposes.”

Crittenden went beyond the immediate question of black colonization to declare that his election would signal a new birth of white supremacy in Kansas City. Rejecting previous white politicians’ willingness to make limited compromises with black Missourians in return for political support, he announced that his administration would make a decisive break with any potential quid pro quo with the black community by purging black men from public employment. In particular, he announced that he would not permit any “negro foremen.” “I do not believe in a negro being a ‘boss’ over a white man,” Crittenden told an audience on March 25, “and I promise you here and now that when I get into office there is going to be a mighty lopping off of heads along this line.” Crittenden’s close friend and political ally, William S. Cowherd, a former congressman and Kansas City mayor with aspirations for the Missouri governor’s office, bolstered these claims by asserting that Crittenden was man enough for the job. Cowherd described Crittenden as “a good man, a man who has the backbone and courage to do right and a man who will do things,” adding, “we want no mamby-pamby [sic], molly coddle in the mayor’s office.”

White Republicans and their allies struggled in their efforts to deflect these charges because of their unwillingness to engage in tactics they found distasteful, but also because they shared some of the basic assumptions about the existence, if not the consequences, of black corruption and criminality. In the wake of the alleged outbreak of black crime, the Republican-leaning Kansas City Star acknowledged that “bad niggers” were responsible, but it also feared unfairly punishing the “decent, respectable negro members of society.” Instead, it recommended an indirect approach to the problem, emphasizing the need for reforms within the black community to address “parents . . . too poor or vicious to have the guidance of the young ones.”

In addition to its racism, this Republican strategy seriously underestimated white residents’ feelings of insecurity and their willingness to project those fears onto the city’s growing black population. As the Democratic campaign gained momentum, the Post began publishing letters claiming to be from white Republicans who had abandoned Beardsley in favor of Crittenden and his racial policies. On March 23, the paper printed a letter to Crittenden from a white Republican “clerk” who had shifted his support to the Democratic candidate. The problem, the anonymous white clerk explained, was not job competition per se, but the relationship between the prestige of patronage employment, higher wages, and “social equality.” According to the clerk, he had paid “hard earned money for a nice home,” only to have “a negro” buy an “adjoining” property. Now, the clerk not only feared for the safety of his “daughters who are just out of their teens,” but he was also unable to move. He laid the blame for the situation squarely at the feet of “[the] city hall machine, [which] by giving negroes public offices encourage them to believe in racial equality and then they buy homes near us.” The “solution,” he claimed, was a residential segregation ordinance, which he believed most likely under a Democratic administration.

Once again isolated from their erstwhile white allies, black Missourians struggled to construct defenses against the renewed threats to their community. For some members of the city’s black middle class, the best defense (for themselves and the community as a whole) was to concede to the terms laid out by white opponents of disfranchisement—including the Star—and to publicly demonstrate their opposition to the alleged criminals in their midst. Other black Missourians abandoned caution in favor of a more aggressive and oppositional stance. On March 20, 1908, the Post published the alleged confession of E.W. Clemmons, a black man charged with illegal registration. Clemmons claimed to have been pressured into voting illegally by black Republicans who had insisted that it was the duty of “[every] colored man in Kansas City to register” in opposition to Crittenden and his promised purge of black Missourians from municipal employment. According to these black Republicans, black men who avoided this obligation “should be taken back down South where they haven’t either the right to register or vote.”

In the Kansas City municipal elections of 1908, Crittenden defeated Beardsley with a plurality of almost 1,350 votes, and the Democrats captured the city council. Although representatives of the Democratic “boss” factions were largely silent during the campaign, they acknowledged Crittenden’s success in the election’s wake. James Pendergast, for example, remarked approvingly on the lack of black Republicans parading through the streets, as often happened following their party’s victory.

From Kansas City to Jefferson City: The Campaign for Black Disfranchisement in Missouri

Crittenden and his allies (Cowherd especially) soon began to contemplate the possibility that their local victory held “at least a state-wide significance.” Not only would Democratic control of Kansas City politics increase the likelihood that the party would carry the city and county in the next statewide election, but they also believed their successful use of race to overcome factional divisions suggested a winning strategy for regaining Democratic dominance in the state as a whole.

Their hopes for the future came from growing support in the wake of their success in Kansas City. In May, Crittenden noted that Democratic “friends” had advised against his repudiation of black voters because it was not the “popular thing.” After the election, however, they had come around to his position. In the weeks that followed the election, the Post announced an ever-growing list of politicians (and prospective politicians) who openly endorsed literacy tests and other legal restrictions on black voting rights. Moreover, as had happened in the Kansas City municipal election, support for disfranchisement at times even crossed partisan lines. On May 19, the paper reported that a study of “[22] young men from various parts of the state, taking examinations for admission to [the] bar” in Jefferson City had found that 20 supported some unspecified form of “restriction,” one opposed it, and one registered as “non-committal.” Of these 22, 13 identified as Democrats and 9 as Republicans, with one of the Republicans opposed and one of the Democrats uncommitted.

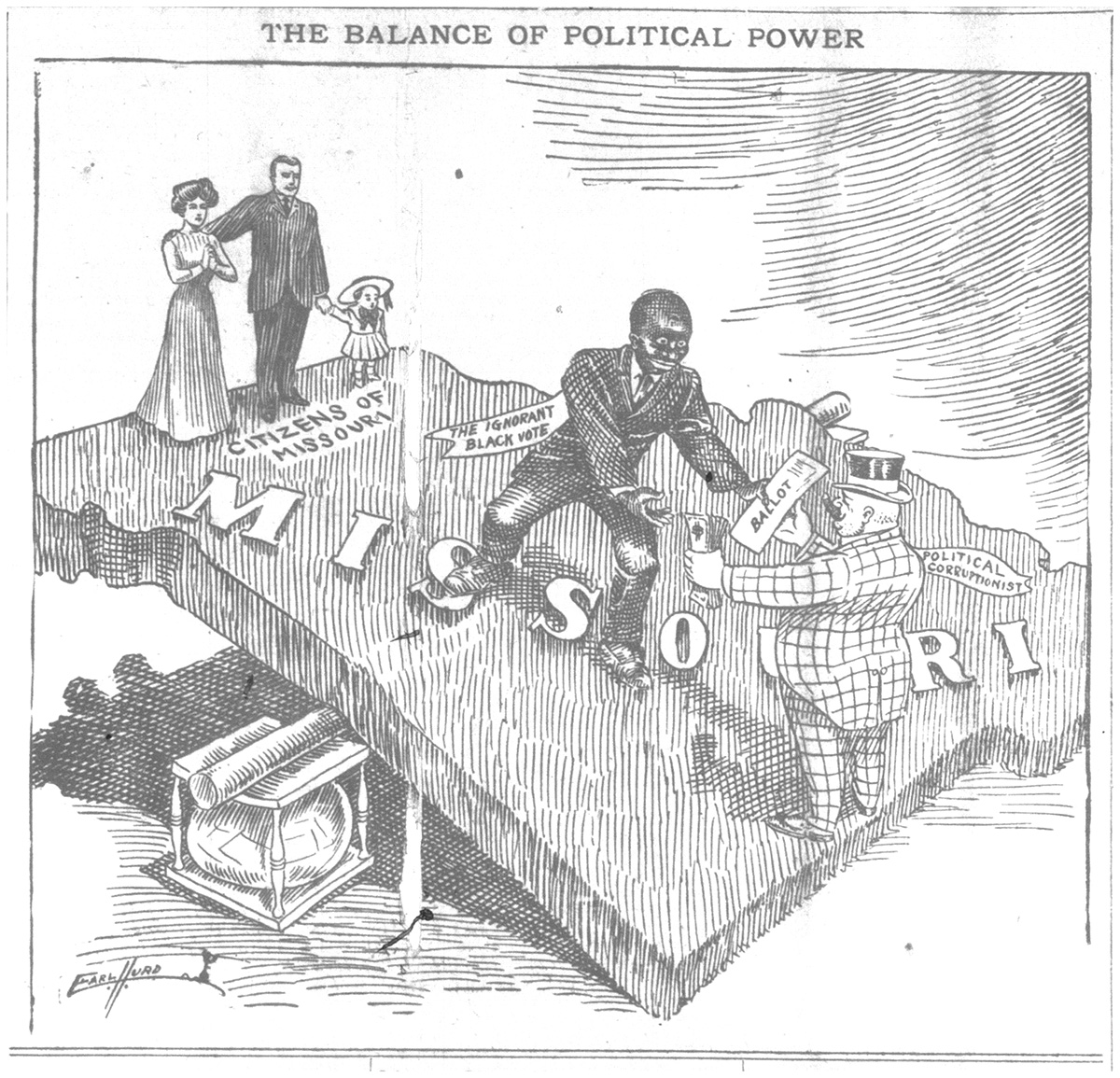

Bolstered by these expressions of political support, Cowherd and Crittenden led the effort to place a black disfranchisement plank in the state Democratic Party’s platform. On May 14, Cowherd delivered a speech in St. Louis in which he declared that black disfranchisement would be a major part of the political program with which he hoped to capture the governor’s office later that year. Calling on white Missourians and party members to “rally to the flag of Democracy,” he reiterated the argument that the success of racial segregation and disfranchisement across the South was pushing black criminals into Missouri. Once inside the state, he believed they easily became the tools of corrupt white politicians and a threat to white women and good government. Sounding a warning to black Missourians and a challenge to the assembled delegates, Cowherd declared, “This is a white man’s country and the negro must be taught to cast both an intelligent and an honest ballot, or must surrender the suffrage he has so long sought.”

While Cowherd attempted to spread the gospel of black disfranchisement in St. Louis, Crittenden led the disfranchisers at the state convention in Jefferson City, where he introduced a resolution committing “the Missouri state legislature, and . . . the people of Missouri, to so restrict the right of suffrage in this state that the ballot will be denied to the ignorant, the vicious and the criminal of the negro race.” Crittenden’s Fifth District delegation adopted the resolution with only one dissenting vote, and it quickly garnered praise from delegates from across the state. Over the course of the convention, the Post recorded expressions of support for general educational tests and the restriction of “negro suffrage” from numerous delegates and party notables. But even with this broad base of support and “a sharp fight over the question” in “several districts,” the proponents of suffrage restriction were unable to convince a majority of the Resolutions Committee to recommend the measure.

The source and strength of this unexpected opposition became apparent when Crittenden attempted to go around the committee’s decision and present the resolution as a minority report to the assembled delegates. Although the vast majority of delegates appeared to have accepted the assumption of black inferiority that lay at the heart of the report, white Democrats ultimately approached the reality of suffrage restriction through the lens of their own political self-interest. At the lead of the anti-disfranchisement forces was Alexander Monroe Dockery, a former governor and longtime representative from Northwest Missouri’s Third Congressional District. Although he “[admitted, in reference to the 15th Amendment] that the enfranchisement of 4,000,000 blacks by the stroke of a pen was the greatest crime of history,” Dockery decried the minority report as an “innovation” that was both unconstitutional and unnecessary. “If some negroes are criminals,” Dockery noted, “the law of Missouri now disfranchises them, as it does all criminals.”

Other Democrats expressed concern that many of the state’s white voters might be removed from the rolls in the effort to disfranchise black men. As Thomas A. Dunn, an assistant reporter to the Missouri Supreme Court, told the Post, “I think the proposition is good enough, but I am afraid that it will lead to such a restriction that later a property qualification will be required for voters. It is difficult to restrict the right of suffrage without danger, because the precedent thus established might lead to greater restrictions.” Still others opposed Crittenden’s proposed restrictions because they had found methods by which to attract, cajole, or fraudulently add black men’s votes into the Democratic column. For example, J.V. Conran, a delegate from New Madrid County who had earlier supported Crittenden, now argued “that the blacks were voting the Democratic ticket in New Madrid . . . and he didn’t want to disfranchise them.” According to the Republican-leaning St. Louis Star and Chronicle, “[the] St. Louis members of the committee on resolutions backed up Dockery in his contention,” because “[the] Fourth and Twenty-second district negroes are needed by the Democrats.”

Finally, delegates from outside Kansas City may have resisted a measure that seemed poised to catapult Democrats from a competing part of the state into power. In May, Cowherd still had several competitors for the party’s gubernatorial nomination, and competing delegations, especially those from St. Louis, had little incentive to commit the party to a policy with which he was identified, especially when it might also undermine their own local political options. Although many, perhaps even a majority, of delegates favored some form of expanded suffrage restriction, Crittenden and his allies failed because they could not agree on the precise method, extent, or target of disfranchisement, and no statewide party leader was willing or able to overcome these divisions and unite the party around a common program.

The disfranchisers continued their fight into the fall of 1908, but the measure was quickly buried amid growing party infighting. By November, Democratic factionalism had undermined black disfranchisement (instead of the other way around), and black Missourians once again swallowed their growing frustration to vote with the Republicans in the face of a clear and present threat to their interests. In October, the New York Times reported that Republicans claimed to have registered “10,000 negroes who have never voted before in Missouri.” On election day in Kansas City, the Post noted that black voters came out for Republican gubernatorial candidate Herbert Hadley in large numbers, but the paper doubted that they could overcome what it predicted would be a “Democratic landslide.” Instead, it was Hadley who was swept into office, defeating Cowherd by a significant margin. Likewise, the Republican candidate for president, William Howard Taft, took the state’s electoral votes, and Republicans carried a majority of seats in the state house. Democrats held the senate and many county level offices, but papers across the state interpreted the results as a stinging defeat for the party at the hands of corrupt politics, Democratic factionalism, and black voters.

The Legacy of Crittenden’s Disfranchisement Campaign of 1908

Far from quieting factionalism and providing a firm foundation for Democratic as well as white supremacy, the 1908 campaign divided the party and united its opponents. In its wake, Democratic leaders quickly retreated to a position from which they could at once remove the issue from factional squabbles and allow for maximum flexibility when dealing with black Missourians in the future. They found this new position during the 1910 statewide elections, when Governor Hadley attempted to rally black Missourians at the polls by stressing the recent Democratic attempt at disfranchisement. Led by Kansas City “boss” delegates James Reed and Joseph Shannon, Missouri Democrats endorsed a plank in their party’s platform denying that the party had ever attempted black disfranchisement. In accordance with their 1910 plank, “[The Democratic Party] never has discriminated and will not discriminate against the colored race, either by criminal laws on the question or their right to franchise, and we deplore the action of the present chief executive of this State in seeking to make political capital by creating race antagonism.” Such a dramatic (and arguably shameless) refashioning of the party’s history was an implied repudiation of Crittenden, who declined to seek reelection in 1910 and lived out the rest of his life in relative obscurity, dying in Kansas City in 1938. But the lessons of his failure appear to have lived on in the Democratic Party that emerged after 1911, one controlled by James Pendergast’s younger brother, Tom, who had served as street superintendent under Crittenden.

Even as Tom Pendergast overcame party factionalism and asserted Kansas City’s influence across the state, as Crittenden had tried and failed to do, he did so not through the mechanism of southern-style black disfranchisement legislation, but through a reconstituted urban liberalism. Indeed, in many ways, the politics of the “Pendergast years” harkened back to the model practiced by his brother and other Missouri Democrats between the ratification of the 15th Amendment and 1908. On the one hand, Pendergast’s liberalism could offer significant gains to black people in return for political support—arguably more than ever during the 19th century and certainly more than existed under the conservative Democratic regimes that controlled most of the former Confederacy during the early 20th century. On the other hand, like boss-directed urban liberalism in Chicago and other northern and border cities, Pendergast’s brand of racial patronage politics was a far cry from genuine, independent black political power and, for decades, left unresolved many aspects of white supremacy, especially in housing, employment, and education.

In the forty years between 1908 and 1948, the distance between the Kansas City of Crittenden and that of Pendergast became the distance between the southern, Dixiecrat conservatism of Strom Thurmond and the "northern," urban, Democratic liberalism of Harry Truman. But their common roots—in a postwar Democratic Party struggling to square the values of white supremacy with the political and legal legacy of Reconstruction—also established what would become the commonalities between black freedom struggles, North and South. Or, as a young black woman told a reporter during the uprising against yet another liberal regime in Kansas City in 1968, "If they’d been through the hell we’ve been through, they wouldn’t be sitting up on no pedestals."

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.