The Politics of Maternalism and the Kansas City Athenaeum Club

“Amazonian furies, bearing aloft insulting banners, marched against the White House, posted their pickets and declared a state of permanent siege.” In 1925, this is how Missouri Senator James A. Reed described those who had agitated for women's suffrage; a “band of spinsters” is how he described those working for passage of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act in 1921. Reed did not think highly of women demanding more of their government, and his attacks offer a glimpse into how women’s growing participation in public life was an evolving and often contentious issue. At stake was the long-held belief that a woman’s proper place was strictly in the home.

In Kansas City, local women’s clubs had for years remained reticent to enter the political fray. Formed originally as literary societies, most women’s clubs avoided the ire of men like Senator Reed by confining their activities to those that were deemed appropriate for wives and mothers to perform. The Athenaeum, formed in 1894 and one of the city’s oldest women’s clubs, provides a representative case study in this regard. Convened originally for the purposes of self-improvement and education, the club was lauded by librarian Carrie Westlake Whitney as one that “promote[s] mutual sympathy and united effort for intellectual development . . . and the higher civilization of humanity.”

Over time, though, the women of the Athenaeum gradually became more comfortable with direct political confrontation, going so far as to directly attack Senator Reed and others who opposed their projects in the pages of Kansas City’s newspapers and at club forums. To address charges that their femininity was compromised by political activity, these women utilized a politics of maternalism to achieve their reformist goals. By emphasizing their fitness as wives and mothers to weigh in on matters pertaining to the family, club women advocated successfully for progressive reforms during the 1920s.

American Women’s Clubs

The history of the women’s club movement in America provides helpful context for evolving societal attitudes toward women’s participation in public life during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When the first women’s clubs formed in the late 1860s, they functioned primarily as apolitical, literary societies or benevolent organizations designed to provide relief to the most impoverished members of their communities. This work toward individual and community improvement was understood as an extension of a woman’s domestic duties and therefore acceptable for her to perform. After all, it was widely held that an industrious and well-read wife and mother would be better equipped to care for her family and raise healthy, educated children. This, in turn, would produce faithful and competent citizens, positively impacting the community as a whole.

Dominant social thinking around a woman’s proper role in society at this time has been described by historian Barbara Welter as the “Cult of True Womanhood.” Under this rubric, a True Woman was one who possessed the “four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity.” Consequently, early community efforts led by club women were narrower in scope than they would later become, constrained as they were by such gendered ideals.

By the turn of the 20th century, increasing numbers of American women counted themselves members of one or more clubs. Although early club membership tended to be exclusively white, Protestant, and middle- or upper-class, the national zeal for women’s clubs gradually extended to include historically excluded and marginalized groups, often through separate organizations. This included religious, racial, and ethnic minority women as well as those who had to work to earn a living. Another significant shift occurring in women’s clubs during the early years of the 20th century was an increasingly open embrace of pro-suffrage sentiment.

Although the ideals of True Womanhood still held sway with many Americans and set expectations for female behavior well into the 20th century, more and more women began to agitate for the right to vote. Significant among their numbers were club women. As support for passage of the 19th Amendment continued to grow, so too did the number of women and clubs willing to speak out publicly in its favor. This was quite a change from the early days of groups assembled strictly for literary discussion or benevolent societies providing aid and comfort to the poor. Yet it was precisely this prior experience in women’s clubs that afforded many women the opportunity to learn about current events and issues, gave them a platform through which to speak out publicly, and helped them develop the skills necessary to organize themselves effectively.

Establishment of the Athenaeum

Organized in 1894 by a group of prominent club women in Kansas City, the Athenaeum is one of the oldest such groups in the city’s history. On the day the call was first made to form the club, as many as 58 women pledged to help organize it. Enthusiasm for the club took off quickly, and by 1914 the Athenaeum was able to fund the construction of a magnificent Greek Revival style club house at the corners of Linwood Boulevard and Campbell Street, where it still stands today. By the time women had won the right to vote in 1920, the group’s ranks had swelled to as many as 500 dues paying members.

Though not all women’s clubs made the shift to become more directly involved in local and national politics, many did. Kansas City was no exception. The Athenaeum club mirrored the national trend toward more direct political engagement. From their origins as a study club, this group of women eventually involved itself in affairs of city, state, and national concern. Leading the charge on many of these issues was charter member and one-time president Phoebe Jane Ess. Because she was more outspoken about her progressive beliefs than many other club members, Ess was able to lead the way and steer the formerly sedate Athenaeum club in a more politically active direction.

The club’s transition to more explicitly politicized speech and action was not necessarily a quick or a smooth one, however. Club records and meeting minutes reflect the internal debate that club members had over whether it was advisable to speak out on controversial political issues, or whether their involvement would spark unwanted backlash. Ultimately, newspaper accounts from the 1920s show that the Athenaeum club did indeed become more vocal on matters of municipal reform and on issues pertaining to public welfare during this time. By leveraging their status as respectable wives and mothers, club women (both nationally and locally in Kansas City) successfully advocated for reform legislation without sacrificing their status in the domestic sphere.

Women Voters, Activism, and the Politics of Maternalism

At the national level, club women were busy coordinating their reform efforts. In November 1920, representatives for several of the nation’s largest women’s clubs and organizations met in Washington, D.C., to discuss how women might collectively exercise the power of their votes moving forward. What emerged was one of the most formidable forces in American politics over the next 10 years: the Women’s Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC). In a book exploring the history and legacy of the WJCC, scholar Jan Doolittle Wilson writes that these women recognized the pursuit of their reform agenda legislatively would require the continued cooperation of America’s club women, just as with the fight for suffrage. At this meeting, partisan loyalties were critiqued as divisive, and women’s solidarity was emphasized as the best strategy for exercising political influence. Doolittle Wilson relates that at this first meeting, Maud Wood Park, president of the newly created League of Women Voters, “proposed the creation of the Women’s Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC), a large umbrella organization intended to unify and to coordinate the legislative agendas of the nation’s most prominent women’s organizations.” It did not take long for these organized women to leave their mark on Washington. Doolittle Wilson also explains, “five years after its inception, the WJCC served as a lobbying clearinghouse for the political agendas of twelve million women representing twenty-one national organizations . . . and was recognized by critics and supporters alike as ‘the most powerful lobby in Washington.’” That is a remarkable distinction, indeed, for a group of women who only five years earlier gained the right to vote.

There are several factors that help explain the broad influence and success of the WJCC in its early days, but most significant by far is the group’s reliance on maternalist rhetoric and politics to achieve their legislative goals. Thanks to contemporary social mores that held that a woman’s proper place was in the home as a wife and mother (where she could embody those ideals of True Womanhood most fully), organized women could thus emphasize their expertise when it came to lobbying for legislation intended to increase government responsibility in matters of public welfare. In other words, although women were now legally voting—officially sanctioned outside the home and voicing their concerns on the public square—their most successful political strategy involved bringing a bit of the home with them into public life. As wives and mothers, women could highlight their expertise in areas like child welfare or maternal health to portray themselves as uniquely informed and credible authorities on such matters. Additionally, this special status lent a sense of moral superiority to their campaigns. The clearest evidence of their success in this regard is the passage of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act in 1921.

Crafted in response to frighteningly high rates of infant and maternal mortality in the United States, this piece of legislation set up an appropriation of federal funds to be made available to states for distribution of educational materials and the creation of health centers providing pre- and postnatal care. Seen as experts on all matters relating to the home, women campaigned masterfully for this issue. Because of their respected status in the home and new power as voters, women were able to transform formerly private issues, like the health and wellbeing of mothers and children, into matters of public concern. In so doing, these women made the health and safety of the American family a primary issue in 1920s politics.

National Goes Local: The Fight for Sheppard-Towner in Kansas City

The Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act, often referred to as Sheppard-Towner or simply the Maternity Bill in newspaper accounts from the period, was a hotly contested issue in the early years of the 1920s. After the end of World War I, the reformist spirit of prewar American politics was significantly diminished. Prior to America’s entrance into the war, a progressive streak characterized much of American political activism as reformers sought government solutions to social problems created by industrialization, urbanization, and political corruption. Once the United States formally entered the war in 1917, this same impulse resulted in the creation of various government-sponsored programs and agencies intended to aid in the war effort. Doolittle Wilson writes that, “for a time, the war years seemed the pinnacle of progressivism, for the exigencies of wartime mobilization had brought about a tremendous expansion of the federal government and a realization of many progressive goals.”

After the war’s end, however, the vast majority of these programs and agencies were diminished or closed altogether as Americans became increasingly wary of government intervention into private life. Moreover, Doolittle Wilson argues that “the public’s fear of communism in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia . . . led to a red scare in the United States, characterized by a widespread suppression of civil liberties and broad assaults on radicalism and reform in general.” Each of these factors led a substantial portion of the American electorate to distrust progressive reformers and their goals. Consequently, American voters elected a more conservative administration to the White House in 1920.

Years later, the impact of this seismic shift in national sentiment would spell doom for Sheppard-Towner. One reporter for the Kansas City Star noted in 1926 that, “The stand of President Coolidge against further centralization of government at Washington has found an echo in congress in the senate bill calling for discontinuance of grants to the states under the Sheppard-Towner act after three years.” To hear most politicians at the time tell it, they were not opposed to the spirit of Sheppard-Towner or its goals of maternal and infant health; they were simply opposed to federal intervention into state affairs in order to get the job done. In the same article, the author closes the piece by stating “that the states should be left, just as far as is possible, to handle their own affairs. And that means both a check on the extension of the federal aid policy and in some instances, perhaps, discontinuance of aid that is now being allowed.” Though it would not be until 1929 before Sheppard-Towner would meet its ultimate demise, backlash to federal intervention and resistance to big government would prove the consistent challenge reformers faced throughout the decade.

Despite such opposition, however, progressive forces still managed to accomplish quite a bit in the years after the war. Though reformers faced mounting resistance to their political goals in the increasingly conservative 1920s, women proved to be one of the most effective forces for getting progressive legislation passed during this period. The Women’s Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC) made passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act one of their top priorities in its early years. Adoption of the bill in 1921 would surely have been out of reach were it not for two things: the maternalist rhetoric and strategy WJCC lobbyists relied on and the tightly connected member network of locally run women’s clubs who did the same.

The umbrella structure of the WJCC helped to streamline and organize women’s efforts on behalf of Sheppard-Towner, making it easier to mobilize and coordinate women’s groups at the local, state, and national levels. These highly coordinated campaigns resulted in politicians all over the country receiving consistent messaging from their women constituents, voicing support for the Maternity Bill as a unified bloc. Strategies like letter writing campaigns and lobbying politicians directly were used to great effect.

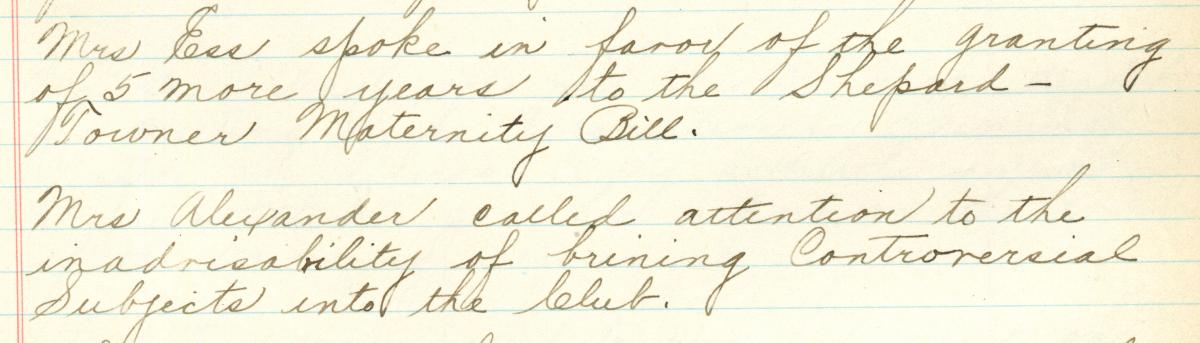

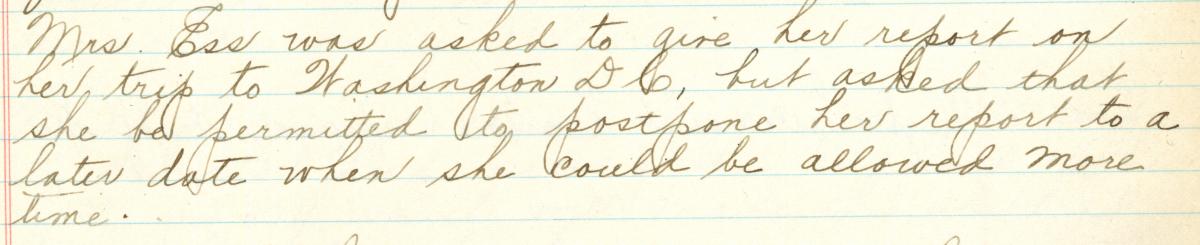

The participation of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) in the WJCC meant that each of its constituent member clubs was also aligned in their strategies as they advocated for the bill. The Athenaeum club was one of those counted among the ranks of the GFWC. This meant that the Athenaeum, along with other GFWC member groups, followed the lead of WJCC leadership in the fight for Sheppard-Towner. Indeed, internal club records indicate that at least one prominent Athenaeum member, charter member and former president Phoebe Ess, traveled to Washington, D.C., to coordinate strategy with the WJCC and report back to club members on the bill’s progress.

The politics of maternalism proved effective in the years after women gained the right to vote with the 19th Amendment in 1920. Locally, Kansas City club women gained invaluable organizing skills and political experience advocating for this measure, which served them well in the later “clean sweep” reform elections of 1940 that finally ousted Pendergast machine-controlled politicians from office.

Maternalism and the Athenaeum Club

Though passage of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act was a great victory for organized women in America, it was by no means their sole focus during the early years of the 20th century. In Kansas City, the Athenaeum club had a long history of advocating for civic reforms as well as public health and safety measures. Though originally founded as a study society and literary club, the Athenaeum’s focus gradually expanded over the years into more reformist areas. Like other Kansas City women’s groups during this time, the Athenaeum’s activities can be charted on a path from benevolent intervention on behalf of those in need to more explicitly activist efforts to achieve reform.

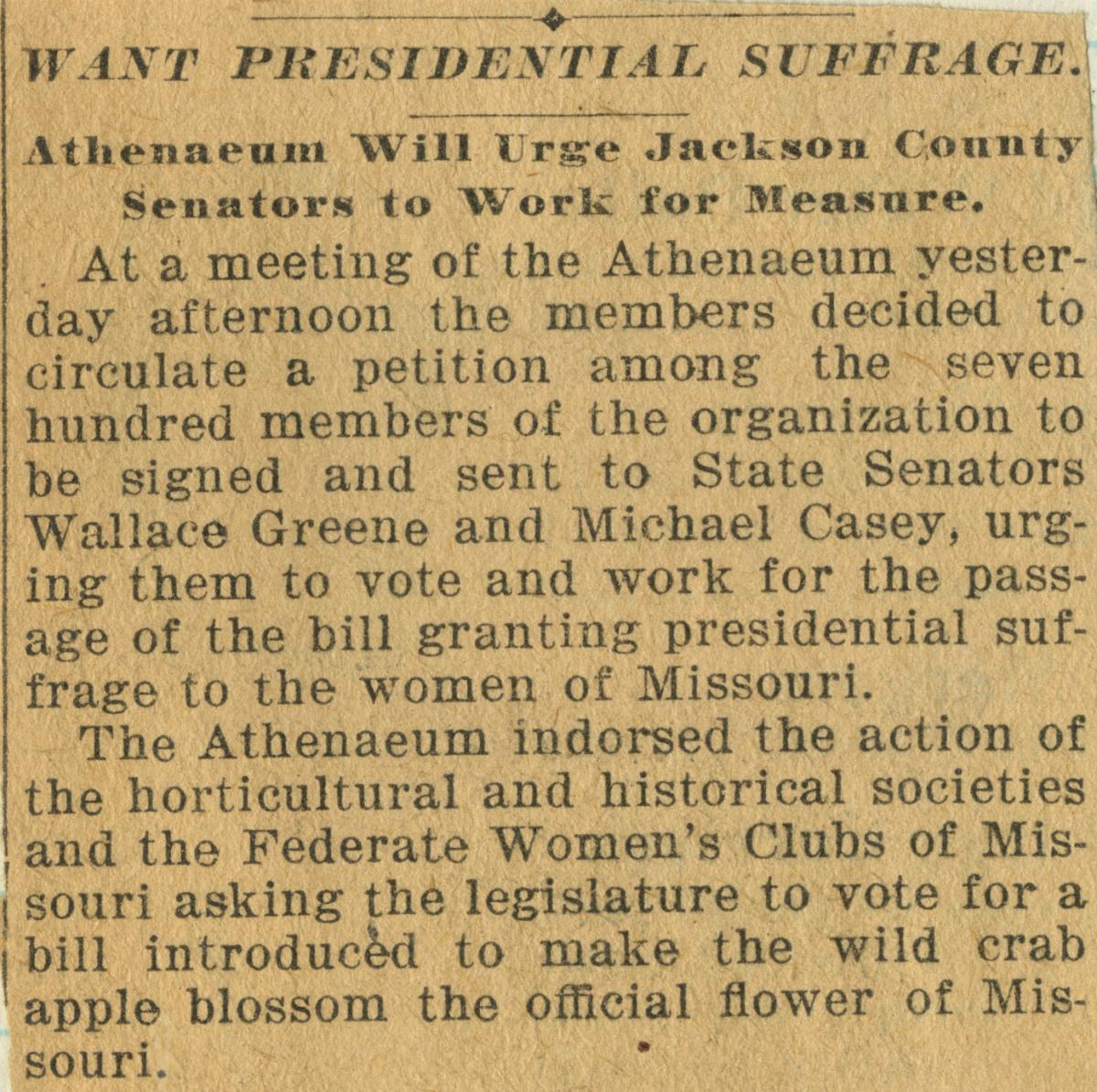

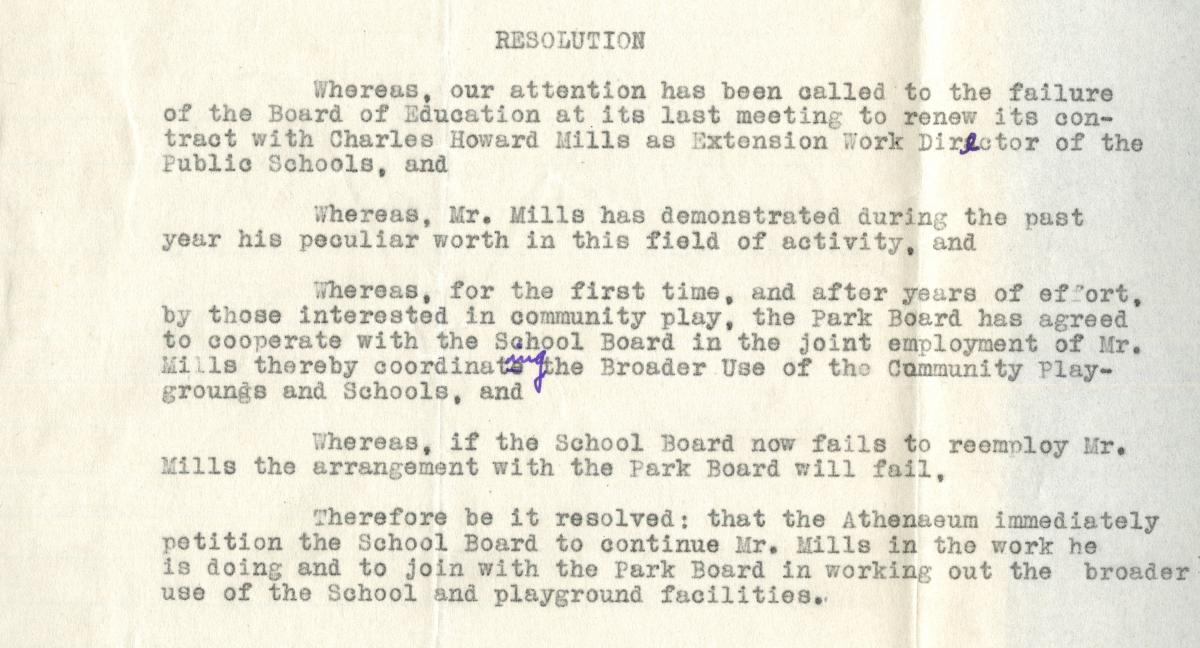

In the years preceding passage of the 19th Amendment, women of the Athenaeum successfully advocated for a number of measures meant to improve quality of life in their growing city. One such effort involved projects focused on the education of children. The Athenaeum worked vigorously to establish kindergartens in Kansas City public schools. Additionally, club members supported the creation of the Mothers’ Union of Kansas City, a forerunner to Parent Teacher Associations in the region. They also worked alongside other federated Missouri women’s clubs to change existing law so that women could be elected to serve on local schoolboards. Beyond educational reform, women of the Athenaeum club demanded that something be done to provide better amenities to Kansas Citians. In their view, improvements such as free public swimming pools, playgrounds, and parks were needed to “draw idle men away from saloons.” Focused as they were on the health and wellbeing of children and family, these public reform efforts are representative of the vast majority of advocacy work performed by club women of the era.

As the years wore on, Athenaeum club members increased their efforts to enact city wide reforms for better public health and safety. Concerned about the quality of milk consumed by families, a group of club women inspected the sanitary conditions of the dairies supplying milk to Kansas City in 1908. Their efforts contributed to a municipal ordinance regulating the conditions under which milk could be processed and sold. Provisions of the local ordinance were adopted by the United States Public Health Service in 1910. Club members also participated in an egg boycott led by the Housewives League in 1913. In 1915 the club coordinated with Kansas City’s National Council of Jewish Women to propose the application of silver nitrate to the eyes of newborns in an effort to prevent blindness, a medically valid method prior to the invention of antibiotic eyedrops.

Though efforts such as these still clearly fell within the province of the domestic sphere, Kansas City club women steadily grew more comfortable with proposing government solutions to what once were considered private problems. Advocating for the health and wellbeing of families and children allowed organized women to begin to flex their political muscles. These accomplishments positioned these same women to advocate, years later, on behalf of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act in 1921. Though their activism may have appeared less direct and confrontational than later women’s reform efforts, club women in Kansas City, through their work in the Athenaeum and elsewhere, were charting a path toward more direct civic engagement in the years before and during the 1920s.

Maternalism and Opposition to Senator James A. Reed

Though club women in Missouri campaigned effectively for the initial passage of Sheppard-Towner in 1921, they certainly faced their fair share of challenges to do so. One Missouri politician in particular was very publicly and staunchly opposed to women’s efforts for passage of the Sheppard-Towner act: Senator James A. Reed. It was no secret in Missouri politics that Reed had never been a friend of the woman voter. He vigorously opposed passage of the 19th Amendment and frequently filibustered debate of the Sheppard-Towner act on the floor of the Senate to delay votes on it. He even attempted to discredit women advocates of the bill by implying they did not meet the ideals of True Womanhood, calling them “cranks, dreamers, Socialists, Bolsheviks, and a band of spinsters.” Beyond the Sheppard-Towner Bill, Reed fought vociferously against passage of almost all progressive legislation aimed at increasing the federal government’s role in public safety and welfare during the 1920s, much of which was supported by organized women. In 1928, the year Senator Reed retired from public office, Paul Y. Anderson wrote of him in The North American Review:

In government, he is a stark Fundamentalist. Regardless of the merits of a bill, he instinctively feels that it should not pass. . . . Although a great lawyer, he regards each new law as a new curse to afflict mankind. If he had his way, I am sure he would repeal three-fourths of the laws on the statute books. His conception of a complete and perfect code probably would consist of the Constitution and the Ten Commandments, and he might strike a few passages out of them. . . . He leans far more upon the wisdom of the past than upon the hopes of the future.

Undaunted in their efforts to secure a better future, Missouri club women organized a robust campaign to oppose Senator Reed when he ran for reelection in 1922. “Rid Us of Reed” clubs sprang up across the state, with some going so far as to stage mock funeral processions for the senator’s political career.

Members of the Athenaeum club also pitched in, endorsing a number of resolutions on behalf of their 500 members and making clear their opposition to Senator Reed’s stand on a variety of issues. These resolutions were often sent to the Senator directly and were also broadcast to Kansas Citians through local newspapers. Phoebe Ess, who was also active in other Missouri women’s clubs, penned an especially stirring call to her fellow women voters in a July 31, 1922, issue of the Kansas City Star:

To the women of Missouri: This is the first time you have had the privilege of voting in a primary election. Tomorrow let every woman go to the polls and cast a vote for the man or woman she wants to be a candidate for office. . . .

We are Democrats. We urge the women Democrats to consider very carefully the names that appear on the ticket for United States senator. Mr. James Reed’s name will be on the ballot.

I have fought the battle of woman suffrage from the first, because I believed it to be a matter of simple justice. Mr. Reed fought against it to the end and voted against it. . . . Why does Mr. Reed ask the women of Missouri to cast their maiden ballot for him? Is Mr. Reed a good Democrat? If so, why did he oppose the great Democratic measures in congress, namely:

The selective draft.

The food control during the war.

The federal reserve bank act.

The eighteenth amendment.

The Sheppard-Towner maternity bill and the league for peace?

The Women’s Long-for-Senator Club.

By Mrs. Henry N. Ess, Chairman.

It is a testament to the power and influence of Kansas City club women that despite winning statewide reelection to his senate seat in 1922, Senator Reed did not carry his hometown of Kansas City. The women of this city mounted an active and influential campaign against him, barring him from earning the support of what should have been his most faithful constituents.

Such training would prove crucial to the eventual rooting out of corruption in Kansas City politics. In the run-up to the reform elections of 1940, club women constituted an integral part of the coalition that brought about the end of years of machine rule. Women were called upon to work the phone banks to remind Kansas Citians to get out and vote, to drive fellow women voters to their polling stations, and even to monitor polling stations for signs of cheating and corruption. Without their tireless efforts, the 1940 election may not have been such a resounding success for reformers in the city. And without their earlier training in how to campaign for change through women’s clubs, these women may never have felt prepared to become involved at all.

This essay was developed as part of an Applied Humanities Summer Fellowship, cosponsored by the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.