From Proscenium to Inferno: The Interwar Transformation of Female Impersonation in Kansas City

The Orpheum Theater, the most opulent playhouse in Kansas City, opened the day after Christmas in 1914. The exterior of the new showplace on Baltimore just south of 12th Street was wrapped in terra cotta formed to resemble Tennessee marble, inset with panels depicting symbols of music and dance. The same terra cotta arched over the lobby’s mosaic marble floor. The leather-upholstered mahogany seats were arranged underneath a 40-foot dome painted to resemble a star-filled sky. Enormous columns supported the domed ceiling in the main auditorium and every seat had an unobstructed view of the stage.

The rarefied venue drew a correspondingly exclusive crowd of civic, business, and cultural leaders. The tony Kansas City Club reserved the entire sixth row for its members every season. Much of the entertainment was vaudeville, as the national Orpheum circuit was one of the country’s leading vaudeville producers. Treading the boards alongside the traditional bumbling comics, lovelorn songsters, and amazing magicians who regularly performed was another, perhaps now unexpected type of act: female impersonators. These characters were a holdover from minstrelsy: the first minstrel impersonator is recorded in 1835, and they were a standard feature on the vaudeville stage. During the 1890-1930 heyday of vaudeville, a number of female impersonators enjoyed impressive, successful careers and became household names across the country. Even during 1920s Prohibition, the tradition expanded into nightclubs and cabarets and drew enormous crowds in large cities like New York and Chicago. American entertainment tastes started to become more conservative, repressive oversight of liquor consumption followed Prohibition’s 1933 repeal, and female impersonation almost immediately disappeared from “legitimate” and cabaret stages throughout the United States. But in wide-open Pendergast-era Kansas City, female impersonators remained popular until the late 1930s.

Vaudeville theater was a reaction to the bawdy, boisterous, adult-oriented entertainments found in 19th century American music halls. US industrialization provoked widespread relocation of rural families to urban centers, and theater producers hoped to tap this growing market for family-friendly fare. Tony Pastor is often credited as the “father of vaudeville,” launching Tony Pastor’s Opera House in New York in 1865 to produce shows advertised as “fun without vulgarity.” Pastor had come of age in music halls and bars so it seems inevitable he became an actor and master of ceremonies. He was a member of the temperance movement and had little tolerance for unseemly behavior either onstage or off. His enormous success with the Opera House and subsequent venues led other theatrical entrepreneurs to follow his lead, and by the mid-1880s vaudeville was an established entertainment style. Pastor and his competitors were influenced by the efficiencies and standardization of Gilded Age manufacturers and the scientific management craze. They created theater-management systems that were unique to vaudeville: they treated it as show business. Their employment infrastructures, booking and management methodologies and networks of circuit touring were completely new to the industry. These nimble techniques enabled them to react quickly and decisively to changing audiences’ demands.

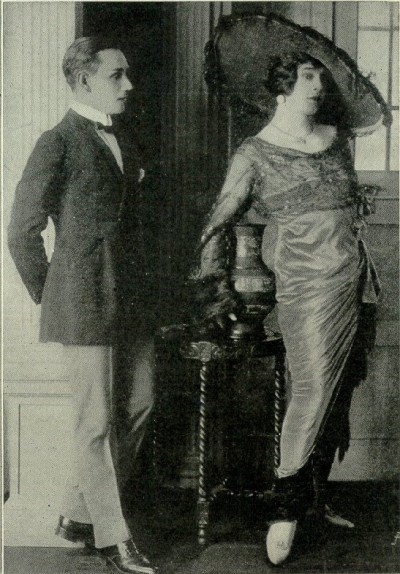

Given that the primary emphasis of vaudeville was “good clean fun,” regularly-featured female impersonators might surprise some modern readers. Vaudevillian impersonators occupied a world apart from 21st century drag queens. Their performances were typically incorporated into skits or longer theatrical pieces that ranged from exaggeratedly comic to empathetically tragic. Many were singers and became well-known for their high-quality acts. The nature of the circuit system–houses in cities large and small across the country–allowed for the popularity of female impersonation to permeate US entertainment culture. Various vaudeville histories record approximately 135 entertainers who were either full- or part-time female impersonators. Of these, around 35 are known to have performed in Kansas City on the circuit, and they played a number of different theaters, including the 9th Street Opera House, the Coates House, the Doric, the Empress, the Gillis, the Globe, the Grand, the Loew’s, the Majestic, the Orpheum, and the Shubert. The range of styles of these impersonators was as broad as the houses in which they appeared, including actors who donned dresses for short bits to those who were onstage in female clothing for the entirety of a show. They were such a regular presence that noted local theatrical photographer Orval Hixon included them in his portfolio. Kansas City theatergoers were fortunate to have experienced shows that featured the two most famous female impersonators of the day, Julian Eltinge and Bert Savoy. These two actors were enormously talented and they each represent diverse and contradictory facets of the art and culture of impersonation.

Julian Eltinge trained as a dancer in the Boston area. His extraordinarily graceful movement and style led his instructor to encourage him to take up professional impersonation. At this time, impersonators fell into two camps: the broadly comedic and the perfectly passing illusionist. Eltinge focused on the latter and was immediately successful, performing costumed and choreographed vignettes in larger vaudeville shows. He polished every detail to maintain his illusions, including costume, hair, make-up and movement. He also spent enormous sums on clothing and accoutrements. His natural soprano vocal talents lent even more authenticity to his performances, and the quality of his illusions and his performances were legendary. By 1910 he had reached a peak in vaudeville. One leading critic considered him “as great a performer as there stands on the stage today.” That same year he was offered and accepted a role in a full-length Broadway musical comedy. This launched a new chapter in his career that ultimately led to silent films in Hollywood.

Eltinge’s success expanded beyond stage and screen into popular consumer culture. His costume and makeup skills resulted in women seeking his expertise in dress and presentation. In 1913 he launched The Julian Eltinge Magazine and Beauty Hints, a nationally distributed fashion magazine that lasted for three issues. He even had his own line of make-up products. The Kansas City Star featured an interview with him in which he berated women for their lack of fashion sense. He claimed that if he could dress alluringly, so could they.

Despite his mastery of an illusionary feminine ideal, Eltinge was markedly uncomfortable with his chosen trade. He gave interviews with members of the press in which he repeatedly complained about having to go to such great lengths to make a living as an impersonator. A large man—he stood 6’2” and weighed 240 pounds—it is easy to understand the difficulties of his stage preparation. Yet his discomfort extended beyond the change in his appearance, and he took great pains to ensure that his audiences understood that he was, indeed, acting. Offstage he affected the demeanor of a paragon of masculinity stuck in the unfortunate job of playing a woman. Eltinge staged many photo opportunities that portrayed him performing quintessentially masculine acts such as chopping wood, fishing, hunting, or engaging in fistfights. When stagehands and the occasional audience member directly questioned his masculinity, he threw his fists in earnest. Eltinge did whatever it took to distance himself from the perceived effeminacy associated with his profession, lucrative as it may have been.

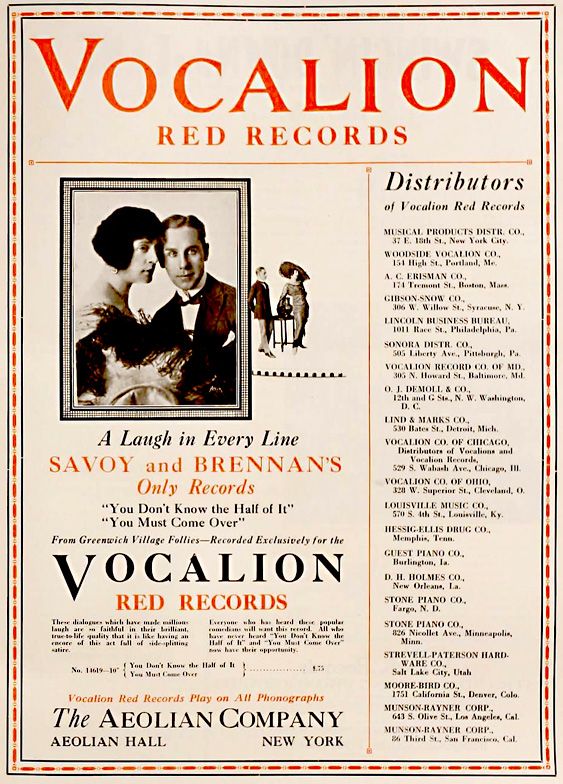

At the opposite end of this feminine/masculine dichotomy, so feared by Eltinge, was Bert Savoy. Savoy’s shtick with partner Jay Brennan was to play the dim but witty woman campily repeating gossip she had heard from her friend “Margie” to Brennan, who played the straight man, literally and figuratively, in the act. One of their stories featured a girl on a date at a chic restaurant replete with dim lights, soft music, and chilled wine. Her date noted, “I’ve never been in a place like this before” and Savoy exclaimed, “My God! I’m out with an amateur!” Another anecdote noted a showgirl who, having recently seen the latest Hollywood version of The Three Musketeers, spied a copy of the book in a shop window and exclaimed, “Ain’t the printing press wonderful—they’ve got the book out already.” Savoy had a supply of stock phrases that were long associated with his character such as “You must come along,” “You don’t know the half of it, dearie”, “My nerves is all unstrung”, “You slay me”, and “You must come over”. Some claim that Mae West appropriated aspects of Savoy’s style and phrasing into her characters and classic lines.

While clearly more lowbrow than Eltinge, Bert Savoy was just as attentive as his famous competitor to wardrobe and other components of illusion; he just carried them out in a much more outrageously comic fashion. Unlike Eltinge this outlandishness extended to Savoy’s off-stage persona as well. He regularly employed feminine pronouns when referring to himself and a cadre of like-minded friends. Unlike other professional female impersonators of the day, he remained in costume and in character offstage. Even the end of his life came in a masterfully ironic moment of camp bravado. On June 26, 1923, Savoy and a colleague were strolling on Long Beach in California when a thunderstorm erupted. After an exceedingly loud clap of thunder, Savoy was reported to have declared “Mercy, ain’t Miss God cutting up something awful?” An immediate bolt of lightning struck both Savoy and his companion dead, ending an illustrious career in style.

Of the two performers, Julian Eltinge was by some accounts more popular with Kansas City audiences. He appeared onstage in Kansas City four different times between 1913 and 1921. At one point a local theater gossip columnist asked readers, “Are you a partisan in the bitter costume rivalry between Dorothy Jardon’s ‘dazzling array of gowns’ at the Orpheum and the ‘wardrobe of ultra-latest models in gowns’ worn by Julian Eltinge at the Shubert this week?” Following his migration to motion pictures, Eltinge’s films enjoyed long runs at movie theaters throughout the city – they ran continuously for nine months in 1917-18. In contrast Savoy and Brennan appeared in Kansas City only once, at the Orpheum in February 1917. The piece they presented was called “On the Rialto” which contained the line, “You can do things in Greece that you can’t get away with here.” Opportunities for female impersonation in the Savoyan vein expanded through the 1920s beyond the vaudeville stage and onto the floors of the speakeasies and cabarets that blossomed across the country under Prohibition, which existed in the United States from 1920-1933.

Great swaths of the US population ignored the restrictions on alcohol consumption mandated by the 18th Amendment, and nightlife became virtually criminalized. Historian George Chauncey noted about New York, “the proliferation of illegal speakeasies and nightclubs after Prohibition led to the wholesale corruption of policing agencies…more distressingly…the popular revolt in New York against the aims and tactics of Prohibition undermined the moral authority of such policing altogether.” Loosened moral restrictions on the part of authorities spread to consumers of nightlife as well. Club goers across the country were more receptive to alternative forms of entertainment than ever before. This was particularly evident in the popular acceptance of gender impersonation.

Typical for such American cultural fashions and trends, New York was the center for the most visible manifestations of drag in cabaret society. Masquerade balls known colloquially as “drags” had been a staple of the city’s homosexual underground since the late nineteenth century. They grew more popular among broader audiences and evolved a sort of cachet during the open years of the 1920s, especially in Greenwich Village and Harlem. By the latter years of the decade enormous balls were held every other month throughout midtown Manhattan. In Harlem, the drag balls were known for the diversity of races, classes, and sexual orientations of their audiences. Press coverage of the Harlem festivities was regular and wide-ranging, largely in papers published by and for the African-American community.

There is no evidence of such large-scale drag balls in Kansas City during this period, but there are numerous published references to cabaret-based female impersonators during the Prohibition years. Musicians who performed in clubs during this time recounted seeing such shows at different venues in downtown Kansas City. The Paradise Club on 15th between Olive and Wabash had two floor shows each evening, both of which featured “a dozen gay transvestites: dancers, paraders, and female impersonators who worked for a producer who originated their routines and coached the dancers. The musicians and the gays got along fine; we used to visit their dressing rooms on our breaks, just to sit and watch them swish and carry on.”25 Trumpet player Booker T. Washington described impersonation at the Spinning Wheel, 12th and Troost, noting that,

the place consists more of female impersonators…that was featured. Each of them would do something different. They had a special to do, each one of them…they dressed like women. They stayed dressed like women. They went around throughout the crowd as women. You know and they didn’t, wasn’t nothing funny or faking with them, they were genuine. They were hired…they had between six and eight of them and they worked every night…In fact, the most of them, that’s where most of our money came from, the impersonators. They’d go out and do their numbers, and they would get tips and what tips they’d get, they’d throw in the kitty [a cat-shaped receptacle used to collect tips].

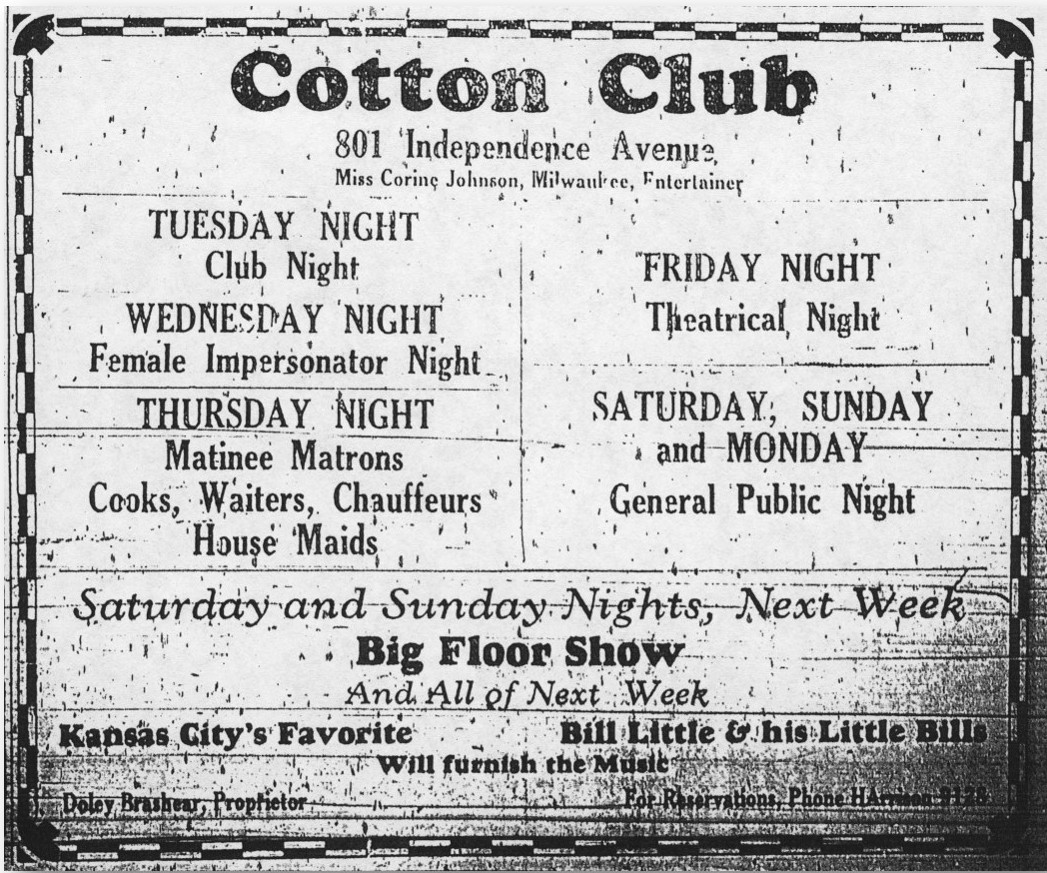

When asked about local floor shows, Saxophonist Herman Walder noted, “they had female impersonators, mostly . . . they was sharp, too, man . . . One of them was named Billy—that’s the one I’d like to have a fight over . . . they would come from out of town . . . song and dance . . . they had all kinds . . . all kinds of artists.” Later Walder described the scene in greater detail: In the black clubs they had female impersonators’ night . . . on Monday—so and so’s night—Tuesday—so and so’s—next was Men’s night—next is sissy night—they’d come on out then . . . female impersonators, they’d come on out…and everybody else, they’d come see ‘em dance . . . .” The acceptance of the impersonators by Walder and other musicians was common: “ . . . we judge people by what they want to be themselves, you dig what I mean? And those people were good—they’re always good to you . . . They’d fill up the kitty, man—if they make some money man, they’d come and fill up the kitty.”

While club band members may have approved of the performing female impersonators, audience members who appeared in costume were not as welcomed. A January 1927 issue of The Call related an account of the arrest of several men in drag at a local nightclub, indicating the dismissiveness they sometimes encountered. The sarcasm of the newspaper account compounds these sentiments:

‘Sissies’ Brought in by Rude Police; Fined $500 Each by Judge

‘It was just too terrible, my dear!’

‘The rude police have no sense of propriety’, let the ‘sissies’ of the city tell it. When the officers of the law raided a cabaret at 1520 East Twelfth Street, early yesterday morning, terror and consternation spread from manly breast to manly breast underneath the frilly garments of the feminine sex, worn for the evening’s pleasure.

When the last screams and squeals had coyly come forth from the throat originally designed from some he-occupation like calling hogs, the police had seven men—six were all clad in dainty chiffon things, cute little pumps, silk hose, and other frills.

Yesterday morning the sight of six men in flimsy clothing evidently had a bad effect on Judge Carlin P. Smith because he fined each of the frequenters $500 each and also fined Ben Payne, the proprietor of the place $500. They are the heaviest fines ever assessed against frequenters of a cabaret.

This event is a rare incident of Kansas City police action against a social transgression in a city that was rife with similar violations of the law. The implied flagrancy of the arrested individuals and the reporter’s reaction to it is a harbinger of shifting attitudes that emerged with the repeal of Prohibition toward female impersonation and other forms of non-normative behavior.

With repeal in 1933, government authorities assumed oversight of liquor manufacturing and distribution. They also gained greater social control over the spaces in which liquor could be consumed. The wild abandon and underground character of the speakeasies of the 1920s was severely restricted and eventually disappeared; nightclubs assumed an aura of middlebrow respectability. Accompanying this influx of middle class values was disdain for the confusion of femininity and masculinity that female impersonators represented. As oversight and authority returned to the cabaret experience, representations of normalcy began to be preferred.

Cities across the United States had either legally banned female impersonation or audience tastes had driven drag from the cabaret scene by the mid-1930s. Raids on drag clubs in Los Angeles resulted in arrests of both performers and audience members. In Chicago, clubs were routinely harassed and even closed with the support of Mayor Edward J. Kelly. Female impersonators at the Garden of Allah in Seattle were replaced by honky-tonk fare. In New York, the nexus of the “pansy craze,” attitudes that arose during the Mae West brouhahas continued to expand, culminating in a 1931 campaign by local newspapers against clubs that featured female impersonation. This led to police crackdowns on individual clubs and eventually on the drag balls in Times Square. Smaller cities became more restrictive, too. Impersonators were actually chased out of Renneslaer, New York, Milwaukee, and St. Paul in the first three months of 1935.

Like many of these cities, Kansas City’s liquor control ordinance was revised in 1934 to reflect the post-repeal regulatory environment. Given that the city remained enmeshed in the Pendergast machine, these revisions were largely for show. Social life went on as before with the added benefit that since he controlled city officials, Pendergast had an easier time controlling the distribution and sale of liquor. The relatively free flow of alcohol resulted in the expansion of Kansas City’s already burgeoning nightclub businesses. Jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams recalled, “I found Kansas City to be a heavenly city – music everywhere in the Negro section of town, and fifty or more cabarets rocking on 12th and 18th Streets.” According to journalist Dave E. Dexter, Jr., one section of 12th Street “boasted as many as 20 saloons and niteries in a single block.” Unlike other, more restrictive cities, numerous Kansas City clubs continued to offer female impersonation among their entertainment repertoires.

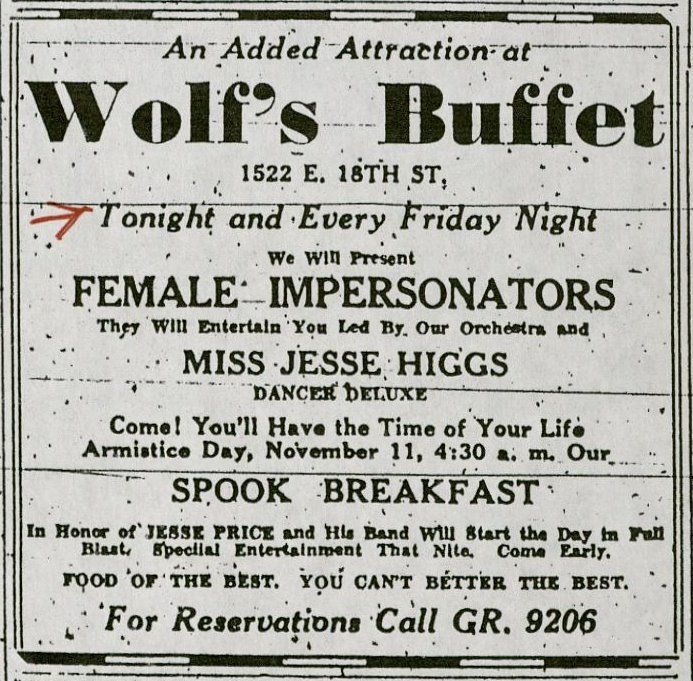

Many of these venues were on the east side of downtown, in and around the 18th and Vine district. At the Eastside Musicians Sunset Club, located at 12th and Woodland and billed as “a show place of the city,” Tuesday night was female impersonator night. The “Sepia Mae West,” on tour from Chicago, had an indefinite engagement at the Harlem Nite [sic] Club in the summer of 1935. During that time she was also the featured performer at the grand opening of the Lone Star Garden at 1708 E. 12th Street, and several days later the highlighted act of the July 4 Dance at Paseo Hall, featuring Bennie Moten’s band. Friday nights were devoted to drag at Wolf’s Buffet at 1522 E. 18th Street, and by 1938 small-scale drag balls were presented at the Lone Star.

Despite the abundant drag shows on the east side, in other parts of the Kansas City community the distaste for alternative expressions of gender paralleled similar attitudes in other cities where female impersonation had disappeared. An unnamed reporter for The Future, a short-lived local conservative newspaper published in the mid-1930s, recounted an excursion into the “second-class Kansas City night club” scene. This rare account is worth quoting at some length:

We decided to make a calm, fairly sober analysis of this second rate phase of our city’s night life; of those small, prolific places that bloom and fade rapidly despite the protection afforded them by the police and the powers that be. We started our investigations at 10:30 on a Friday night and closed them with the dawn. We did not go in a spirit of muckraking. We went to see and hear, hoping to find out why so many intelligent citizens spend their money and time sitting in these little unlovely places, breathing smoke and dust, drinking inferior beer and terrible whisky or plain strong alcohol, listening to generally wretched music and watching floor shows that are either embarrassingly stupid or stupidly indecent. We never found the answer, but we submit a detailed report for your consideration.

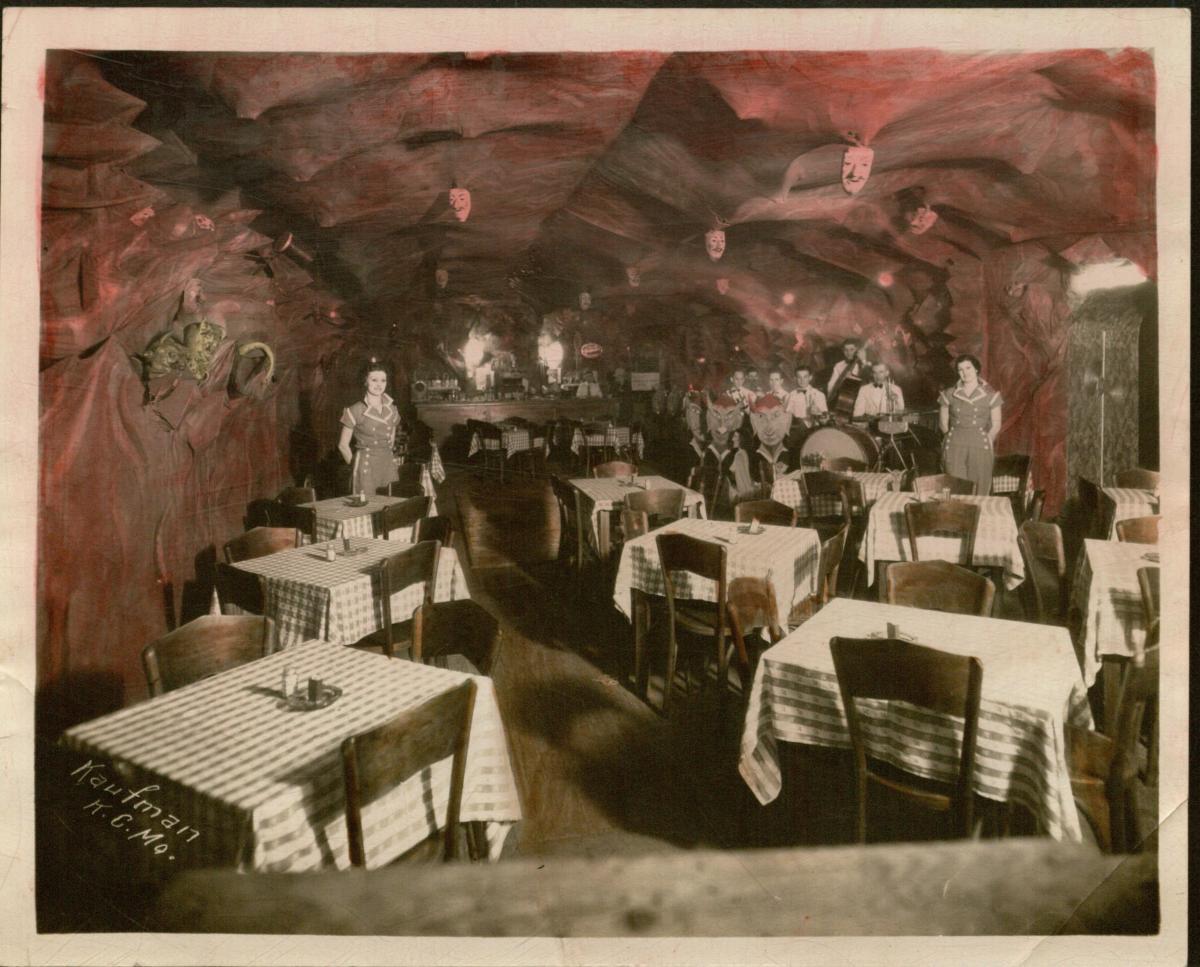

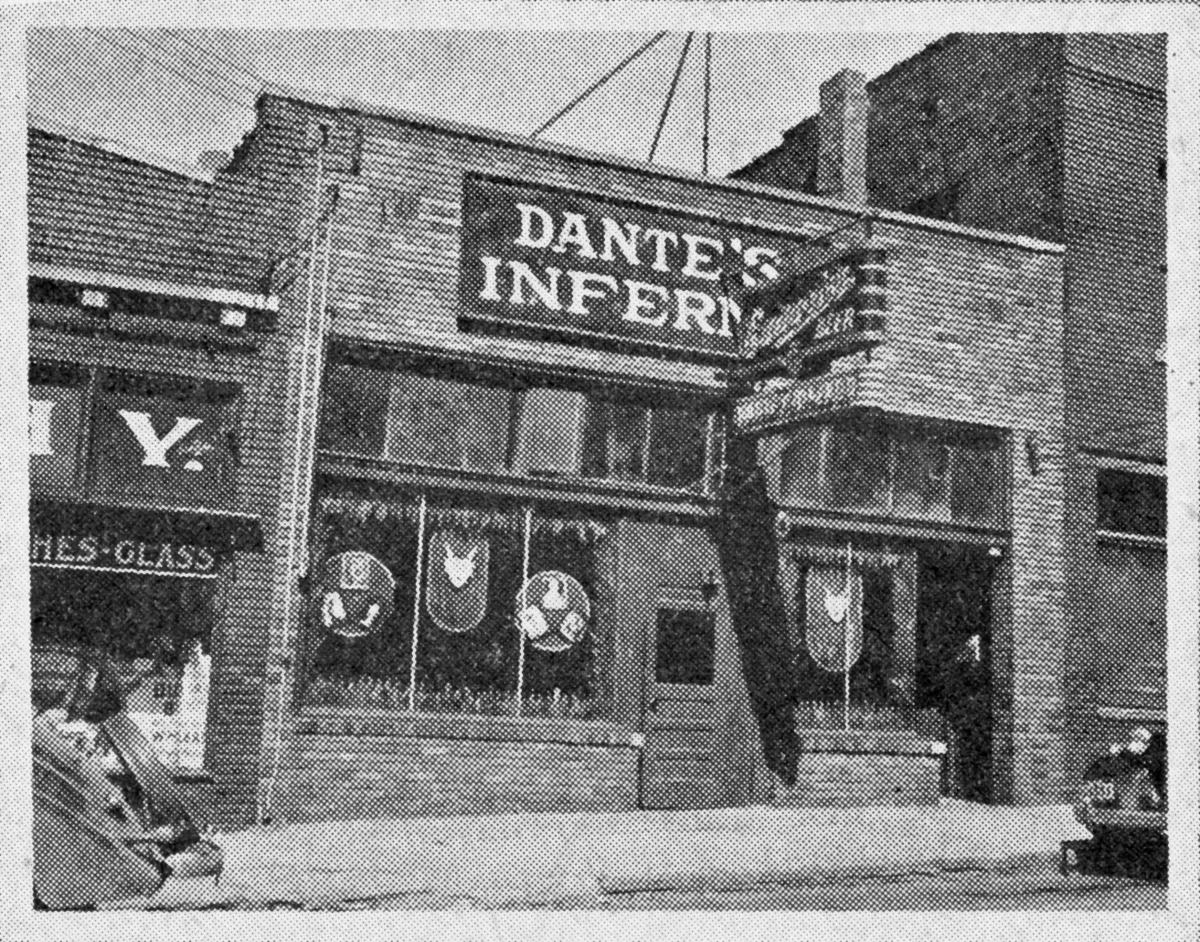

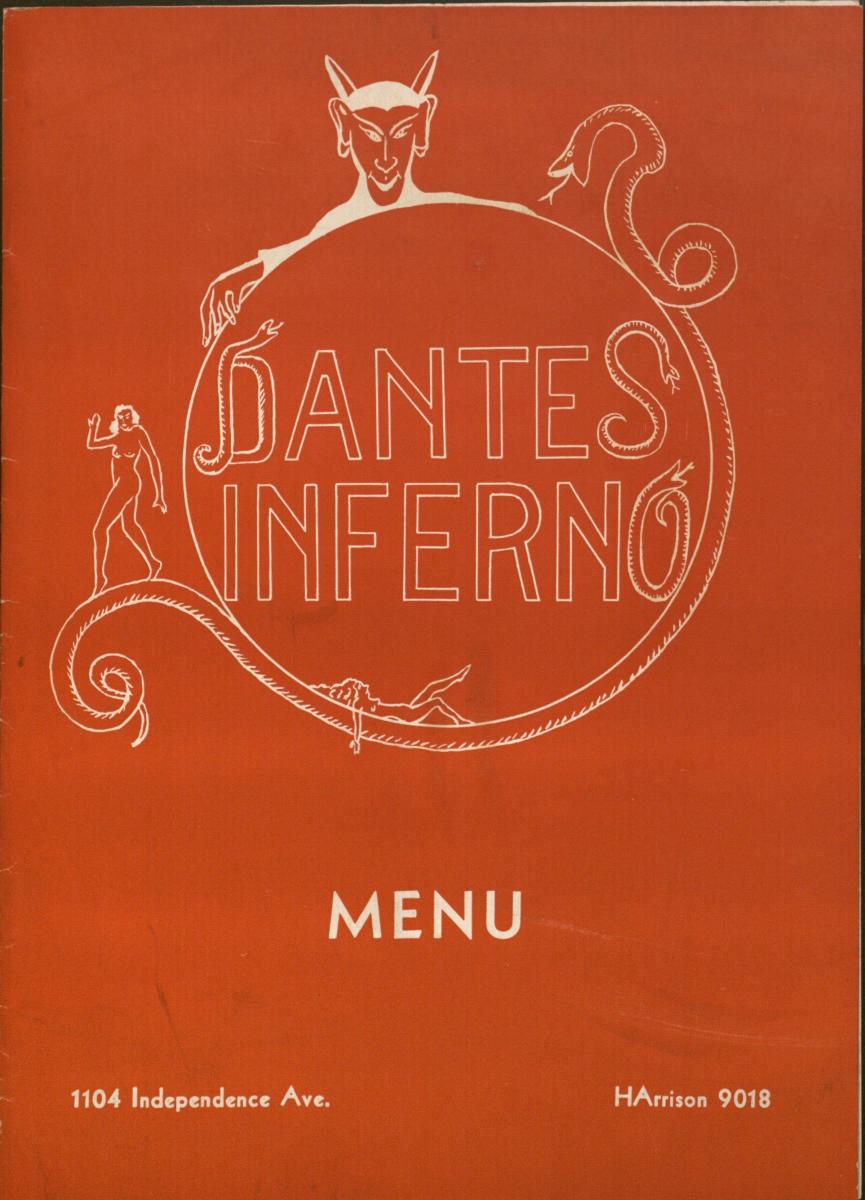

We went first to Dante’s Inferno, a small building with a smaller entrance. The interior is decorated with a lurid red substance which must be as inflammable as the flames of hell it symbolizes. We were there for the first show, and extremely unpleasant ordeal, for the female impersonators who gave it were an inept and pitiful lot. One of them came to our table, sat down in all his finery, and ordered a sherry flip. Kansas City, he lisped, was the crudest place he had ever worked in. “The folks here sure are dumb. They don’t get nothing subtle.” He went on to explain that he worked on a circuit which extended from New York to New Orleans; he made pretty good money, but had to spend a lot of it on snappy costumes. He was wearing, at the time, a little tulle model, decorated grotesquely with a bunch of bananas. One look at the croupiers behind the gambling table decided us against trying our luck there. We left just as the soft-spoken Mr. Lusco was arguing with two young men patrons in an attempt to prevent them from dancing together.

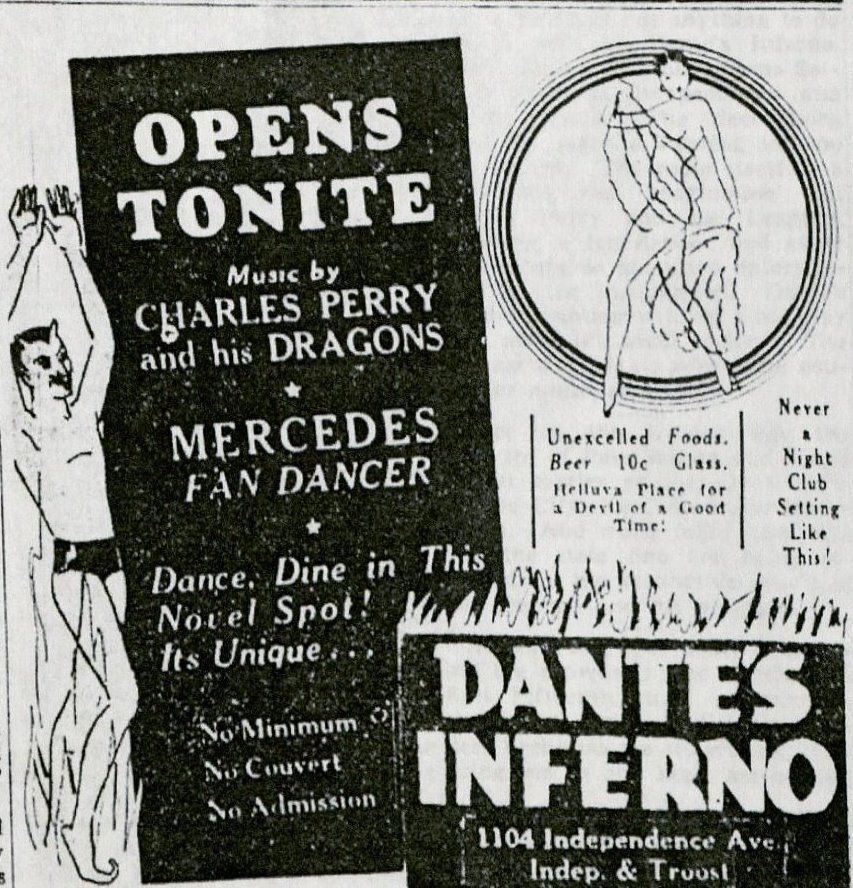

This anonymous foray into Pendergast-era nightlife provides an acerbic introduction to Dante’s Inferno, the Kansas City club that became known throughout the city for female impersonation. Located at Independence Avenue and Troost, Dante’s opened in December 1933 and was billed as “never a nightclub setting like this!” Northside politico Joe Lusco, who had ties to organized crime, owned the club. Eli Madlof was the popular Master of Ceremonies for the floor shows backed by the Charles Perry Orchestra. As the catty Future writer reported, the club was decorated in a hellish theme, with red painted walls to represent Hades and Satanic knickknacks arranged throughout.

The richest source of information about Dante’s Inferno is Edna Mae Whithouse, who performed there. Born in Indian Territory in the first decade of the 20th century, Whithouse and her family relocated to Kansas City when she was a child. They lived in Midtown near 29th and Gillham. Her father was a religious singer, but she took her vocal talents in a decidedly “infernal” direction. She was both a waitress and a regular performer at Dante’s, beginning almost as soon as it opened. The waitress uniform echoed the club’s décor. “We had a little devil suit, and horns . . . we had a tail, but that caused a little business,” she recalled in an interview. “You’d go by with a tray of drinks and some sucker’d get a hold of your tail, so we eventually de-tailed the costumes.” The uniform’s designer also “made the monsters in there, and he made ‘em move…they’d crawl out of the cave…spill somebody’s drink, they’d jump and scream.” As a singer, Whithouse supplemented her serving tips with additional gratuities earned during “table singing” stints, as she called them. “I hustled those songs at tables . . . I’d squat down at the table . . . they always wanted a little sad song, even the gangsters, even the tough guys . . . ,” she recounted. “They’d sit there and blubber, just as tender as babies . . . I’d get as high as a hundred dollars . . . you sing softly enough so if Mr. Jones at the other table wants to hear it he’d have to call you over.”

As part of the floor shows Edna Mae was billed as Eddie and paired in a duo with Seattle-based female impersonator Billie Richards. The act performed regularly, although it is unclear if Eddie presented as a female impersonator. Eventually they became known as the Lynn Sisters and were popular with local audiences and the entertainment press alike. Whithouse described the environment the female impersonators encountered: “When we first got them, they [audiences] were curious. People didn’t know what to make of ‘em. But the longer we had them, the more they liked them. They’d invite them to sit and they’d buy drinks for them.” She recounts that the impersonators encountered difficulties with some African Americans at the club, not indicating whether they were staff or patrons: “The boys would make cracks to them. They slapped a couple of them, which is bad . . . theirs is just a business, it’s nothing personal.” Club management, though, stepped in to maintain order and decorum. “Brother Jim [Lusco] straightened ‘em up. He said ‘Don’t you bother these guys’ . . . the other gays’d come down to see ‘em . . . everybody’d come to see ‘em.” The response of these African American club patrons or staff is in direct opposition to the experiences of the black club musicians quoted earlier. While evidence of these differing responses is lacking, the fact that the female impersonators and the musicians were in professional collaboration may have contributed to the more positive perceptions of the performers.

Whithouse continued to perform at Dante’s well into the 1930s, until she was recruited for a touring company of the Follies of 1936. Around that same time, Dante’s relocated to 512 East 12th Street and discontinued female impersonation in their floor shows. Whithouse returned to Kansas City after touring for a few years, and partnered professionally and personally with Joe Jacobs. In the mid-1940s they opened the Riverside Supper Club at Highways 71 and 45. The restaurant and nightclub were housed in the building that formerly served as the clubhouse at the Riverside Jockey Club, established in 1928 by Tom Pendergast and Phil McCrory.

At the onset of World War II, female impersonation largely disappears from the record of civilian life, although there is a body of evidence demonstrating it was a regular feature of the military experience during the war. By the start of US involvement in the war, a reform government had been installed in Kansas City, which even the apolitical Edna Mae Whithouse described as a “big improvement” over wide-open Pendergast graft and corruption. Kansas City, like the rest of the nation, got down to the serious and deadly business of war. The previous quarter century had presented Kansas City theater and cabaret audiences with local and national female impersonation for a longer period of time than in most other US cities. At war’s end, Kansas City, like the rest of the nation, busied itself with recovery and reclamation of something resembling “normal life.”

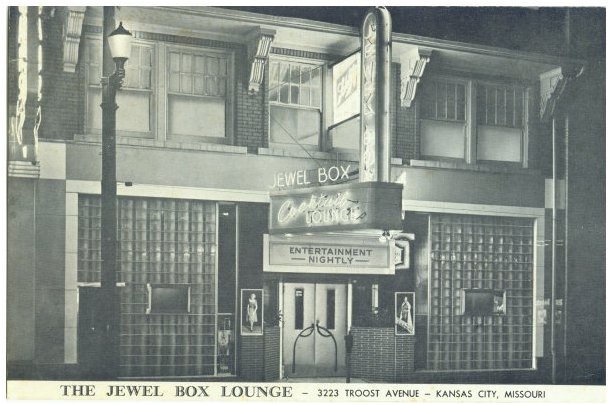

The late 1950s launched a second formidable cycle of Kansas City drag history centered at the Jewel Box, a nightclub at 3219 Troost. The new generation of impersonators at the Jewel Box embodied the shrill, hyper-artificial female characterization popularized by Bert Savoy, and was best personified by drag legend Rae Bourbon. Bourbon was internationally known and previously had been featured at Dante’s Inferno in several performances. According to Whithouse, Bourbon was “one of the world’s greatest...I guess second to Eltinge. He did an awful lot of swishing, but he didn’t wear ‘drag’ – he dressed real classy. How ultra he was! He worked for us [Dante’s] four times – he was a headliner.”61

Throughout his career Bourbon toured the US, and ultimately returned to Kansas City to cap his performing life in the early 1960s. He was regularly featured at the Jewel Box, and released a live recording of a performance there. As an entertainer, Bourbon served as a bridge from the raucous Vaudeville traditions that had kept female impersonation in the public eye to the emerging self-identified gay community of three decades later that found its first home in clubs like the Jewel Box. He contributed to perpetuating female impersonation in Kansas City long after it had disappeared in other cities across the United States, and he provided a direct linkage between these two distinct eras of a hidden Kansas City theater tradition.

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.