Race Relations and Civil Rights

Kansas City’s cultural vitality was made possible in large part by the diversity of its citizens and by the oft-contested relationships among people of minority races and ethnicities. Prominent leaders confronted traditional legal, social, and political barriers. One of them, Lucile Bluford, opposed segregation by applying for admission to the University of Missouri school of journalism and documenting her struggle in one of the nation’s leading African American newspapers, The Call. African Americans and people of Irish, Mexican, and Italian ancestry comprised significant constituencies of the Pendergast political machine, and consequently they were able to exert unprecedented influence on the city’s politics and development.

There remained, on the other hand, strong resistance to racial liberalism. Hopes for true progress were often dampened by the corruption associated with machine politics. A resurgent Ku Klux Klan reached some six million members nationally by the mid-1920s, holding its second national convocation in Kansas City, Missouri, and exerting considerable influence on the Kansas side of the metropolitan area. As Professor Jeffrey Pasley argues, Kansas City’s contested racial and political landscape ushered in the transition of black voters from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party under the banner of the Pendergast coalition, years before the same party realignment occurred nationally under President Franklin Roosevelt.

Featured Article

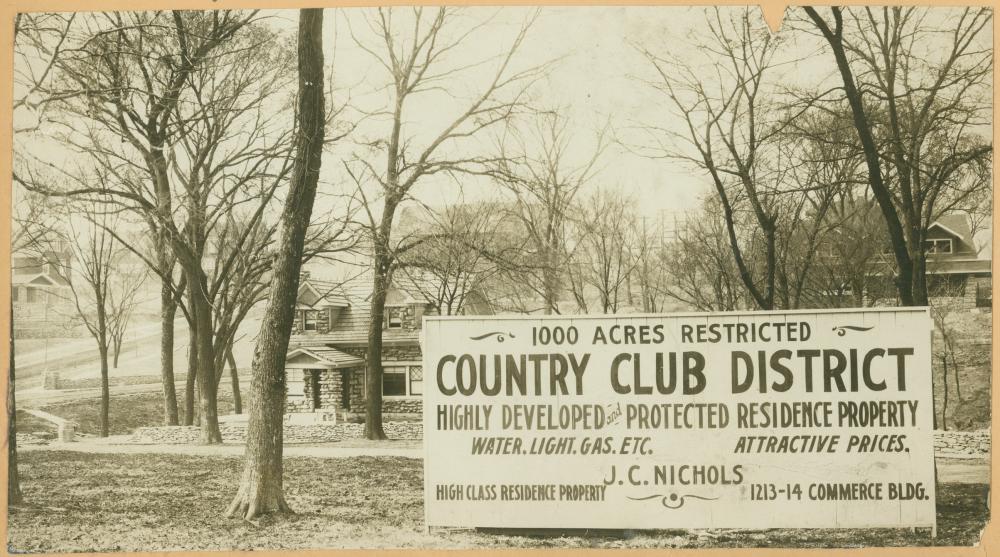

Kansas City, like other American cities, added new suburban-style developments at its edges during the early decades of the 20th century. What makes it a unique case for understanding this shift is the character of Jesse Clyde (J.C.) Nichols. Born in Olathe, Kansas, in 1880, Nichols had a career that spanned the first half of the 20th century, and included transforming thousands of acres of land into a planned suburban community.